Disclaimer: We’re dumb for spending THIS much time caring about laundry. We’re dumb for caring about athletes 100 times more than they care about us. We’re dumb for creating self-serving narratives, searching for bad blood that doesn’t really exist, pitting athletes against one another just because it’s fun to compare them, or judging their entire careers by certain games or certain moments. And we’re really dumb for using words like “we” and “our” and pretending that we’re on the team too.

That hasn’t stopped Patriots fans since 2001 from desperately wanting Tom Brady to steal the “Best QB of His Generation” crown from Peyton Manning. That desire spawned from a bitter place: We immediately resented Manning as our then–AFC East rival, the no. 1 overall pick, Archie’s son, the Golden Boy, the kid designated to be the next Marino even though he hadn’t done anything yet. Our own version of that franchise guy (Drew Bledsoe) hadn’t fully worked out. We hadn’t won a single Super Bowl. We hadn’t won any sports title since 1986. We were pissed about everything. Hating Peyton Manning? That felt right. Let’s hate this guy.

And then … this.

Brady emerged from a generic sports movie script, just a handsome, steel-chinned sixth-rounder holding down the fort for a hopeless team. His first NFL start doubled as a glorious home thrashing of, you guessed it, Manning’s Colts. I was living in Boston that year; suddenly, you couldn’t go three minutes without overhearing a “Brady or Bledsoe?” conversation. Three weeks later, they crushed the Colts in Indy by 21 points — with Brady throwing for more than 200 yards and three scores — and after that, only Bledsoe loyalists cared when Bledsoe came back. Those two Colts games and an unexpected AFC East title put Brady over the top; the Snow Game pushed him to another level; the Super Bowl cemented something well beyond flash-in-the-pan status; and “Brady or Manning?” slowly became a thing.

My generation of Boston fans was weaned on the “Russell or Chamberlain?” question. We backed Russell for obvious reasons, but also because winning mattered more than numbers. Russell was a winner; Wilt was a loser. That’s what we believed. Was it unfair to Chamberlain? I broke down their rivalry for my NBA book and found out that, actually, it wasn’t unfair at all. Wilt WAS selfish. Wilt WAS obsessed with numbers. Wilt looked down on Russell for being so obsessed with winning. Wilt believed that whatever was best for him was best for his team.2 Wilt’s teammates felt like props; Russell’s teammates would have fought to the death for him. Wilt’s opponents thought Wilt was a selfish loser; Russell’s opponents revered him. Everyone from their generation would have rather played with Bill Russell. Everyone.

Boston fans (myself included) desperately wanted Brady-Manning to play out like Russell-Chamberlain. We wanted to pigeonhole Manning as the selfish loser, the numbers-only guy, the one who kept crumbling on the biggest stage. And we wanted Brady to become our new Russell — the “winner” who couldn’t be measured only by numbers, the one who ascended whenever it mattered, the one who kept proving that “clutch” DID exist. But Brady wasn’t quite Russell, and Manning definitely wasn’t Wilt. Their turf war evolved into the finest sports rivalry of the decade, loaded with twists and turns, football’s version of a 15-round war.

Those head-to-head Manning-Brady seasons mirror actual boxing rounds. Manning won 2000 by default. Brady grabbed 2001 (and a ring). Manning took 2002, then Brady roared back for three straight (including two more rings). In 2006, Manning won the fight’s most thrilling round (and his first ring). Brady tagged Manning with the 16-0 season in 2007. Manning won a 10-8 round in 2008 and took 2009 too. Brady won 2010 and took a 10-8 round in 2011. And Manning won 2012 and 2013. That left them tied at seven not-so-fictional rounds apiece heading into 2014. We would “settle” everything in this month’s AFC title game. But they had to survive the divisional round first.

On Saturday, Brady upped the ante with the most emotional home victory since Saving Private Ryan. The Patriots became the first playoff winner to rally from two different 14-point deficits. They beat Baltimore without a whiff of a running game or pass rush,3 which seems impossible, but it happened. They even dusted off a Belichick rarity — the Kitchen Sink — which yielded a momentum-changing drive from a goofy four-man offensive line, followed by Julian Edelman’s receiver-to-receiver bomb that they’d been hiding in Gillette Stadium’s attic for six years.

This was Belichick at his devious best: patching **** together, playing to limited strengths, conceding weaknesses, doing whatever he needed to survive. Baltimore’s banged-up secondary had one undeniable weak link — beleaguered cornerback Rashaan Melvin, plucked off Miami’s practice squad two months earlier — so naturally, the Patriots went after him like Jamie Foxx destroying Doug Williams on a roast dais. It was that kind of game. Scrap, claw, fight, do whatever it takes.

Not counting the three Super Bowls, this was the second-greatest Patriots victory ever, as well as their second-most-exciting victory ever and second-best home win ever. (Trailing only the Snow Game over Oakland in January 2002.)4 And it was the best Gillette Stadium victory ever; by all accounts, the much-maligned Gillette (an acoustic nightmare) turned into Boston Garden during the Edelman-to–Danny Amendola touchdown. The place was shaking. That’s what everyone said.

Meanwhile, Brady hadn’t pulled a playoff victory out of thin air since January 2007, in San Diego, with Reche Caldwell, Jabar Gaffney and Ben Watson as his receivers and Troy Brown playing nickelback.5 Manning outdueled him one week later, just one season after Jake Plummer had handed Brady his first playoff loss. Uh-oh. The following year, the Helmet Catch ruined a possible 19-0 season. Bernard Pollard wiped out 2008, then the Pats blew home playoff games in 2009 and 2010. In 2011, they barely survived the Ravens and gave a fourth Super Bowl away thanks partly to Brady’s semi-shoddy second-half performance. In 2012, Flacco defeated him at home. In 2013, Manning walloped him in Denver.

The Brady Kool-Aid drinkers never discussed our concerns publicly. But privately? We talked about it all the time. We didn’t know if he still had “it.” Those 37 years and 200-plus games had taken their subtle toll. He couldn’t move around or throw deep like he once did. His head-butting, shoulder-slapping, F-bomb-dropping intensity came and went depending on the game. His numbers remained superb, but every so often, he’d miss a simple throw or stumble through a three-and-out and you’d think to yourself, Oh no.

In my lifetime, I watched three legitimately great Boston athletes lose “it” because of injuries: Orr’s knees, Bird’s back, Pedro’s shoulder. Each time, you knew. But Brady still LOOKED like Tom Brady. He seemed healthy enough, keeping himself in phenomenal shape, even revolving his eating/sleeping/working-out routines around football and only football. And he was playing an increasingly skittish sport that protected quarterbacks to comical degrees. Why couldn’t this keep going? Why couldn’t he play through the decade?

After a hideous September culminated in that god-awful Kansas City loss on Monday night, for the first time we seriously contemplated a football future without no. 12. And it was freaking petrifying. You look around and see the Kyle Ortons and Brian Hoyers and Josh McCowns and think to yourself, My God, that’s gonna be us. Of course, we forgot about The Infrastructure. The Brady-Belichick Patriots and Duncan-Popovich Spurs are built like skyscrapers; yeah, they might sway during earthquakes, but they’re never crumbling. How many times have we looked stupid betting against The Infrastructure? Within a week of the K.C. game, New England’s battered offensive line belatedly meshed, Gronk turned back into Superhero Gronk, and our old buddy F-Bombing, Fist-Pumping, Shoulder-Slapping Tom Brady even showed up. Twelve wins, another AFC East title, another no. 1 seed. Lather, rinse, repeat.

And yet … we still didn’t know.

Would you trust 37-year-old Tom Brady if he were trailing by three points at home with less than 10 minutes to go, with no running game whatsoever, while knowing the Ravens would close the game if they got the football back?

We answered that question last weekend: best drive of the day, best throw of the day (the touchdown to Brandon LaFell), total command. Tom F---ing Brady. Just like old times. And here’s the thing: He needed it. He needed a Legacy Game. If the comeback from that ghastly Chiefs loss had already regalvanized (if that’s even a word) every Boston fan behind Brady, then Saturday’s game-winning drive was the belated payoff. It sounds like the chorus to a Counting Crows song, but it’s true — you don’t know what you’re losing until you feel like you might actually lose it.

There was one unforgettable moment, right before the two-minute warning, on a crucial fourth-and-3 for Baltimore coming out of a timeout, when Gillette’s speakers blared a cheesy-but-lovable ’80s song as everyone in the stadium belted the chorus. Nearly 30 years after they peaked, the Outfield finally had their finest moment: 60,000 Patriots fans working off nervous energy by happily belting out the “Your Love” chorus at the top of their frozen lungs.

I just want to use your love … TOOOOOOOOOOOOO-NIGHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHT!!!!!

I don’t want to lose your love … TOOOOOOOOOOOOO-NIGHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHT!!!!!

It was the perfect song for about 30 different reasons, and the perfect moment too. The Patriots ended up getting a stop and winning by four. Tom Brady still had it.

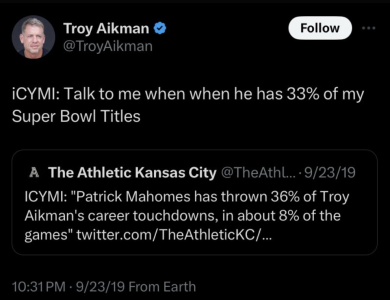

Twenty-four hours later, Brady officially won the 15th round when a broken-down Manning labored through four painful quarters against the Nobody Believes In Us Colts. They treated Manning like NBA defenses treat Josh Smith — basically, they stacked the paint (in this case, the line of scrimmage), left Manning alone behind the 3-point line and dared him to shoot (in this case, throw deep). He couldn’t do it. When it goes, it goes. They built that Broncos team much like the K.G.-Pierce-Allen Celtics were assembled — three contending years, at least, then cross your fingers and hope for one or two more. You need luck to win Super Bowls, and they never quite got it. Now it’s over.

For Manning, the question isn’t “Can I play well anymore?” Of course he can. Steve Nash described this dilemma so eloquently in The Finish Line — Nash knew he could play world-class basketball once a week, but three or four times per week had become impossible. Manning knows his creaky, high-mileage, surgically repaired body can produce world-class football for six to eight straight weeks, but for five straight months? At that position? No way. He’s not done, but he IS done.

And then there’s this: Last weekend, Brady had Belichick, who graduated from the “greatest football coaches ever” conversation and threw his Patriots ski cap into the “greatest sports coaches ever” conversation after that Baltimore game. Manning had John Fox … who “mutually parted ways” with Denver 24 hours after they lost. And if you watched both games closely, you noticed a decidedly different urgency from the Patriots and their fans — they could feel the Grim Reaper coming, not just for that day, but for the entire Brady era. And they ramped it up accordingly.

Compare that experience to what Manning had on Sunday — frustrated fans, receivers jogging aimlessly through do-or-die routes, a coaching staff inexplicably lacking any sense of desperation. Same dire situation, totally different outcome. Manning has played for four coaches; Brady has played for one. Brady’s coach would have rolled out the Kitchen Sink during that Colts-Broncos game. Manning’s coach just stood there and watched.

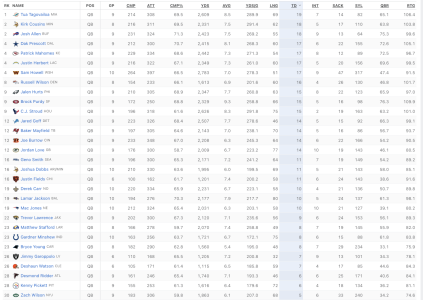

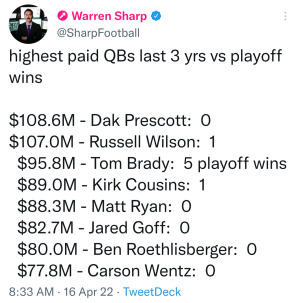

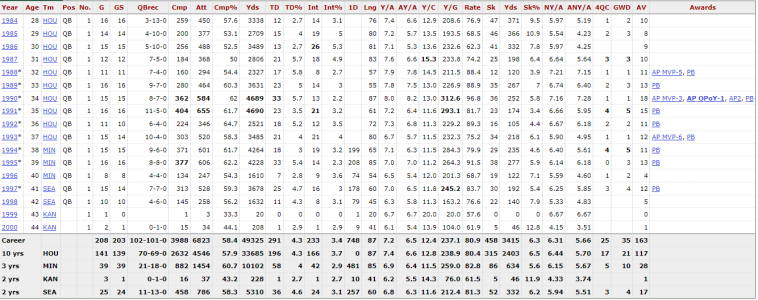

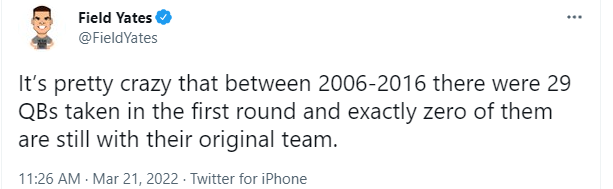

That not-so-subtle difference helped to swing the 15th round, as well as a few of the other rounds. It made up for Brady’s 14-year revolving door of running backs, receivers and tight ends, or all the seasons spent learning how to run a new offense and/or click with new personnel. Now, he’s two more playoff victories away from true immortality: four Super Bowl wins, six Super Bowl appearances, nine AFC title games, the 50,000-Yard Passing Club, the 16-0 season and a staggering playoff record of 21-8 (not to mention nine first-round byes).

Brady had Belichick; Manning had a bunch of guys who weren’t as good as Belichick. It wasn’t a totally fair fight. Forty years from now, I won’t feel nearly as passionate about “Brady or Manning?” as those crusty Celtics fans who staunchly defend Russell over Wilt. Someone will ask Old Man Simmons who was better. I will forget the details and stammer a little. All the games will blend together. I won’t remember who won what and who beat whom. And I’ll probably end up muttering something like, “They were pretty damned close. They were both great. Really great. But Brady had Belichick, and he won more Super Bowls.”

Maybe that’s how this ends, and maybe that’s how this should end. But one other not-so-tiny piece matters here. Manning belonged to Indianapolis, then to Denver, and his career probably ended when his old team vanquished his new team. That’s sports-as-laundry. It’s the very definition of it. Colts fans loved no. 18, now they love no. 12. And eventually, no. 12 finished off no. 18. Laundry.

But Brady accomplished the rarest of modern football feats — he doesn’t just belong to one of the 32 National Football League franchises. It goes so much deeper than that. It’s about what Elway means to Denver and Jeter means to New York. It’s about some imaginary mountain in Western Mass. showing off the heads of Brady, Bird, Orr and Russell. It’s about the most successful football run since Lombardi’s Packers. It’s about one more Lombardi Trophy burying every Spygate joke and every a-hole comment from the Ray Lewises of the world. It’s about holding on to a 14-year run (and counting) that will absolutely, positively never happen again. What are the odds of landing one of the greatest football coaches ever AND one of the greatest quarterbacks ever? Do you know how lucky that is?

Believe me, Patriots fans know. There was an endearing desperation about those last three quarters on Saturday, a vulnerability that hadn’t seeped out before. Over everything else, that’s what caused Belichick to roll out that Kitchen Sink, and that’s what caused Brady to reach back into the vault for that game-winning drive, and that’s what caused 60,000 people to sing “Your Love” a little more loudly than usual. They loved their team, their quarterback, their coach, everything. They didn’t want this thing to end yet. And it didn’t.

So yeah, Belichick can break out his monotone voice and his “On to Indianapolis” routine. But he knows better. And so do we. We’ll always have the Baltimore game. The 15th round was gravy.