Sonja Sohn stood in front of her audience, confident about the performance she was about to give. This wasn’t surprising, considering her history as an actress who was just coming off a five-year run as Det. Shakima “Kima” Greggs on HBO’s “The Wire,” one of the most critically acclaimed shows in television history. To project professionalism, she had pulled her hair back and was wearing pressed slacks and a collared shirt. Her motivation was clear, her research was done, and after many months of preparation, she was ready.

There was no script, though. Her “stage” was a classroom at the University of Maryland School of Social Work, and her “audience” — made up of teenagers and young adults whose lives could have beenmined for “The Wire” — wasn’t about to grant her anything based on her past credits. Not 18-year-old Tyrea Daniels, who guesses he had been arrested eight or nine times by then for selling drugs and stealing cars; 16-year-old Latavia Cornish, who says she was “always outside, stealing, getting locked up”; or 21-year-old Sean Hawkins, who had been “thuggin’ it up” since he dropped out of high school, “selling drugs, partying, stealing, robbing everything in sight.” They and about 15 people from similar backgrounds were slouched in their chairs, warily eyeing Sohn and each other.

This was mid-2009, during the first session of ReWired for Life, a program Sohn had conceived of years earlier and devoted herself to building after “The Wire” signed off. She hadn’t been ready to leave the show behind, neither what it stood for nor the Baltimore streets on which it had filmed. It was more than that, though. “I had an extraordinarily strong sense of purpose,” she says, in the same half-purr, half-growl voice familiar to fans of “The Wire.” “My entire life had become about this.”

All of which meant little to Daniels, Cornish and Hawkins. It was cool to meet Kima because they had loved the show and loved seeing their reality depicted on screen. And free food was never a bad thing. Beyond that, they didn’t expect much. They had all been prodded to come by probation officers, counselors and parents.

“We are talking about a throwaway population that adults think are too far gone,” Sohn says later. “We’re talking about kids that people have given up on over and over and over again. They don’t feel like anyone is there for them. They may have parents who love them, but they’ve been falling back on themselves for so long that if you come in front of their faces talking, and not backing it up with action, you just become another one of the people who have disappointed them.”

Sohn, then in her early 40s, was certain that if the right people came to ReWired at the right time, they could benefit immensely, maybe even transform their lives. She didn’t expect it to happen in that first session, but she believed in herself, she believed in her plan, and she believed that transformation, even here, was possible.

Hawkins, for one, wasn’t buying it. He had grown up near Green Mount Cemetery on the east side, then over by Walbrook Junction on the west side. His father was in jail. His mother and her boyfriend encouraged him, but their voices faded when he stepped out the door and walked past one boarded-up house after another. He was clearly smart, but he quit school because the people he saw getting ahead — getting paid, getting girls, getting respect — were the guys in the game, hustling. After a string of arrests left him facing the possibility of a long prison stretch, however, he began to see things differently. He was about to become a father, and his girlfriend already had another child, meaning he was on the verge of abandoning his kids just like his father had done. He resolved to make changes, but GED programs and job hunting made him feel, he says, like “a blind man in a black room trying to find a black hat.”

Sohn was offering to help, but he figured she must have had an angle. Why else would she be here?

“A lot of the way I live my life has nothing to do with logic,” Sohn says, but Hawkins didn’t know that and didn’t know how committed Sohn would prove to be. Sohn might not have known herself, actually. But she did believe that she could understand what these kids had been through — because she’d been through it, too.

Landing the part of Kima was a huge break, but when filming started in 2002, Sohn was awash in anxiety, forgetting lines, feeling disoriented. She was a professional actress in her mid-30s. She had done this before. This shouldn’t have been so hard.

But “The Wire” wasn’t a typical TV series. Over five seasons, it chronicled the uneven, often quixotic efforts of police, drug dealers, junkies, teachers, dock workers, kids and ex-cons to improve their lots. The show’s writing team, led by former Baltimore Sun staffer David Simon and featuring former Baltimore detective and public school teacher Ed Burns, weren’t trying to create entertainment per se, says Simon, but rather “a dialectic about urban issues and poverty, and the drug war and economics.” They pursued authenticity above all else, ruthlessly refusing to provide happy endings and instead using language, location and narrative to pull viewers into a world of, as Simon puts it, “people who have been separated economically, socially, politically from the rest of America” — and then insisting that we all share stakes in, and responsibility for, the future we are building.

For Sohn, though, the material was “kicking my whole thing up,” she says. She had grown up in Newport News, Va., in an area much like the Baltimore neighborhoods in which “The Wire” was set. Cops were not the good guys where she came from, so even acting the part was unnerving. The show’s broader message made it palatable, says Simon. “I think that was a great relief to her, because I think she had some latent sense of horror that she was going to be working on a cop show as a cop,” but the fractured lives in the script conjured barbed memories. Her father was an African American Army vet from the poor side of Winston-Salem, N.C., her mother a Korean he had met while in the service who had grown up during the worst of the Korean War. Sohn was raised in a public housing project that resembled the West Baltimore low-rises the drug crew in “The Wire” controlled in the show’s first season. There was a good deal of fighting in the streets and in her home. Her father was prone to violent rages during which he battered Sohn’s mother and threatened to do worse.

Home became a place of pure misery, even more so when a babysitter, an older girl, started molesting her. She wanted to run away but didn’t want to leave her mother alone to endure her father’s abuse. Ducking down a nearby alley, she’d write her thoughts on the wall with a broken piece of brick. Or she’d go to a school playground, climb a slide shaped like a rocket ship, and say, again and again, “It’s going to get better,” until one day, better wasn’t enough. “It’s going to be great!” she announced.

“I don’t stay disempowered for long,” she says. But while school, sports and poetry kept her going in her youth, she also started using and selling pot and cocaine. She managed to keep up her grades and hold a job through high school, though, then went to New York, where she started, but didn’t finish, design college. She did, however, fall in love with and marry someone she describes as a nice, stable middle-class guy. They had two daughters together and lived comfortably in Brooklyn, but chaos was never far away. Her drug use continued, and her brother, who had drifted to North Carolina and had his own issues with drugs, was shot and killed after befriending a woman with a violently jealous boyfriend.

Sohn realized she had to make some big changes. Intense therapy and painful self-reflection helped her get off drugs and recalibrate her life. Her marriage didn’t survive, but what she calls her “healing” later involved mending hurts she had both endured and inflicted. Over time, she established good relationships with her ex, her daughters, even her parents — who, she came to think, did their best despite their own tumultuous upbringings.

And she was grateful for her mother’s devotion and the protection she tried to provide (she is now deceased). Sohn was grateful, too, for her father’s encouragement and social justice teachings. He had always discussed the issues of the day with young Sonja, always pointed out political and civic leaders he admired for trying to improve the lives of others. The violence, she believes, stemmed from undiagnosed or mistreated mental illness, an outcropping of his youth — for years, he wasn’t allowed to touch his tuberculosis-ridden mother — and his time in Korea. In later decades, he got treatment, found a supportive church and became a positive part of her life again.

Kima and Sonja persevered together, the character surviving a shooting, the actress settling into her role and then growing more invested in the real-life narratives all around her.

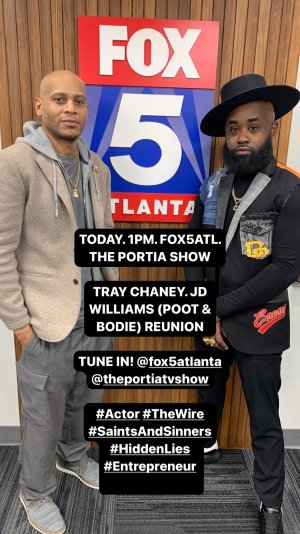

Simon and Burns, who had spent a year reporting on a single drug-strewn block to co-write a book called “The Corner,” were both intimately familiar with the aching desperation and stagnant resignation afflicting much of Charm City. Brooklyn-born Jamie Hector, who played ascendant drug kingpin Marlo Stanfield, ran a nonprofit theater group in New York for at-risk youth. Gbenga Akinnagbe — a.k.a. Chris Partlow, Stansfield’s dead-eyed hit man — was the son of Nigerian immigrants who spent part of his youth in homeless shelters before riding his wrestling skills to college. To them and others, the material was personal and important, part of something larger.

In 2008, after the final season, Sohn, Hector and Akinnagbe went to North Carolina to campaign for Barack Obama. Sohn was stunned to learn that their work on “The Wire” had bequeathed them a platform. “Something happened to her,” Hector says. “I guess she realized the amount of change she could effect in the lives of young folks.”

Sohn started wondering: What if they took “The Wire” into schools, dissected how characters negotiated their environment and got kids to talk about how they did the same in their lives? Could that help them step outside themselves and see how they were making decisions, how there could be other possibilities?

She shared the idea with Simon, saying she wanted to start an organization called ReWired for Change (ReWired for Life is its pilot program). “I was surprised,” he says. Most TV and movie people who adopt a cause, he adds, “say a few words, they’ll go to a dinner, they’ll give some money, but this is time. Time is the ultimate expenditure.” He gave his blessing but worried about how Sohn would raise money and whether she could succeed where even the best-intentioned Baltimoreans had not. “There was a part of me who wanted to put my arm around her and say” — he takes on an almost pitying tone — “you are about to go on a journey.”

Sohn gathered advice and support at the panels and the college classrooms that cast members from “The Wire” were frequently invited to. She cultivated local contacts and tapped Simon and “Wire” cast mates to join the board and give money. A few Baltimoreans held fundraisers. To cover shortfalls, Sohn figured, “I could drain myself until we got this thing off the ground.”

ReWired for Life, she believed, should be community-based and grounded in both social justice and academic theory. Its facilitators needed credibility, so she recruited “Elder” Ted Sutton, who in the late 1980s had been a shotgun-toting lieutenant under legendary Baltimore drug kingpin Melvin Williams but now counseled gang members looking to get out of the game, and Greg “Shamsuddin” Carpenter, a convert to Islam who spent two decades in prison but now helped former inmates adjust to life on the outside.

Both were there when Sohn met Hawkins, Daniels, Cornish and the others for the inaugural session and explained that they were embarking on four 12-week “modules.” Initially, Sohn said, they’d focus on self-reflection, on ways “to become more aware of yourself and your history, and to understand how you got to where you are.” The second module would break down “how you think and how your thinking informs your decision making.” This was greeted with a collective shrug, but she pressed on. “The next couple of pieces revolve around your understanding of the world around you” — relationships and affiliations with everyone from friends and family to congregations and cops — and then “taking that critical-thinking model to the world around you, so you can give back.”

They met twice a week, two hours per day. They watched parts of Season 1, which focused on the drug trade, and Season 4, which centered on the school system. Then, Sutton, Carpenter and Sohn tried to get the participants to discuss what they had seen and relate it to their own lives. Early on, the conversation was muted. That changed after they watched clips from Season 4 during which four eighth-graders — Naimond, Dukie, Randy and Michael — were coming of age and trying to negotiate the streets. The characters were starting to understand what they wanted, what they needed, and the extent to which they were on their own. That day, Hawkins recalls, “we all started to talk.”

Prompted by other episodes and other exercises in the ensuing weeks, they began sharing stories of fractured home lives, friends who had died, close calls and run-ins with the police. They talked about morality, cause and effect, decisions and consequences. Sohn never dismissed their responsibility, but she knew these were people shaped by events that unfolded over generations, people who developed skills they needed to survive, destructive though they may have been. Daniels, for instance, had been in foster care his entire life, moving from home to home, with no money, no real sense of security. “Tyrea has no family,” Hawkins says with astonishment. “I’ve never met anyone who says, ‘I have no family,’ and they really mean it.

“I went out there to hustle because I wanted to, because I felt like doing it. He hustles because he has to. He robs because he has to.”

Daniels himself recalls being urged to stay in school, but school was just another place he had to protect himself. “When I go to school, I got to watch my back,” he says. And after school, “when I walk the streets, I got to watch my back.”

The group dwindled from 20 to 15, then 10. Those who stayed, though, grew more engaged. They knew that Carpenter, Sutton and, especially, Sohn didn’t have to be there. Hawkins says a measure of trust developed. Toward the end of the session, Sohn and Carpenter led a field trip to North Carolina, stopping on the way in Newport News. “She showed us the project she came from, the school she went to,” Daniels recalls. He says it was like she was telling them: “I went through this, I got my [expletive] together,” and they could, too.

The group became its own support network. When Cornish saw her uncle get shot and killed at a barbecue, and when Hawkins’s younger stepbrother and another good friend were murdered while sitting on an East Baltimore stoop, they could reach out to others who understood what they were going through. In times past, Hawkins would have sought revenge, but he had taken to heart the lesson that “the choices you make lead to consequences.” (He says the killer was later killed in prison.)

This wasn’t Hawkins’s last challenge, though. Sohn nominated him for a mayoral anti-gang violence initiative, so he’d be receiving an award at City Hall. On the day of the ceremony, while waiting for Sutton to give him a ride, Hawkins got a call telling him that some guys had gone to his mother’s house looking for his twin sister’s boyfriend. Hawkins didn’t know the whole story, but “my twin sister, that’s everything to me,” he says, the anger rising in his voice as he remembers. “When she calls, I come running, because she doesn’t call me for something small.”

Sutton, an imposing man known as “Crazy Ted” in his gangster days, had gone through something similar when he was getting out of the game. On the eve of his college graduation, his crew wanted him to help take care of a rival. He said no, and the next day got his degree. He channeled that experience to counsel Hawkins, who Sutton could see was enraged and thinking about violence. As Sutton recalls: “I was like, ‘Look, this is that fork in the road right now. You can already play this whole scenario out in your mind like a chess game.’ ” There’d be a confrontation, retribution, and someone would end up dead or in prison.

“The 15 bus is right there,” Sutton told him, pointing down the street. “You can go to your mother’s house. Or you can get in this car with me.” At the end of the day, “you can be looking at your award at home and happy, or you can be down at central booking.”

Sutton’s words pierced Hawkins’s rage. “I looked, and I thought, and I went on and did what I was supposed to do, because any setback would not take me forward in life,” he says. “That would have taken me 10 steps back.”

“The possibility of a different way of doing things — that’s the key piece.” Sutton says. “A lot of them, they don’t even see another way.”

The second group skewed older and had different needs. Nikita Brady was exhausted from years spent on the corners, dealing, fighting, stealing. Her closest friend had been shot and killed. She had been told she could play basketball in college if she could get in, but “I didn’t have that extra push, that motivation, until I met with Sonja,” she says.

“We started to see,” Sohn said, “that although the program is very useful, if you don’t have your GED, and you don’t have a job, and you’re 19 years old, and you’re quitting drug dealing….” She paused. “If in this very moment, you can’t earn money to help yourself, the rest is a moot point.” The participants needed practical life skills they could not learn watching “The Wire” — résumé writing, opening a bank account, handling job interviews, dealing with legal issues.

So Sohn put the third session on hold and started adapting the original vision. But a new opportunity arose. Maj. Melvin Russell, commander of Baltimore’s Eastern District and an early backer, put Sohn in touch with Pastor Marshall Prentice of Zion Baptist Church in East Baltimore. Prentice said Sohn could use a house the church owned farther up East Lanvale Street if she fixed it up. It stood across from two vacant houses, near known drug corners, and it was yet another project to add to her to-do list. But she had long imagined having a house for the program to serve as an anchor in the community ReWired was trying to engage.

Three months later, a large banner hung from the building, welcoming one and all to a free barbecue at the “Village House.” The interior, once dingy and rundown, was now clean, airy and pleasant. Several dozen people gathered out front, and Sohn, in a burgundy dress, buzzed around shaking hands, dispensing hugs, telling people to get something to eat. Sutton was there — when a well-dressed lady said she had come from a funeral, he asked, “Young or old?” Hawkins was there, too. He had found work with a landscaping company but was hoping to find something that paid better. His wife, Shakiara, was about to start a short prison stint for fraud, so it was on him to care for the kids.

Sohn soon started a new gig, too, as Det. Samantha Baker on ABC’s “Body of Proof,” a crime drama filming in Providence. It was a supporting role on a traditional cop show, but it was also a way to keep working and help fund ReWired. She was driving up and down Interstate 95 on a weekly basis, doing her scenes, then heading back to Baltimore. She sounded and looked tired.

Late in 2010 and into 2011, the third session remained on hold, and she was struggling to find the right people to manage ReWired and the Village House. Early in 2011, Daniels got arrested because he had held up an older couple at a bus stop after his foster mother had thrown him out and he had been homeless for several weeks. Sohn was heartened that he called her and said he knew he had done the wrong thing. It showed reflection and accountability, she thought, part of what she had been trying to instill. The group rallied around him, writing to him in jail, sending money, doing whatever they could — while also stressing that he had to make better choices.

One night in March, Daniels, wearing a black Adidas tracksuit, arrived at the Village House for a ReWired meeting. He wouldn’t be sentenced until the summer, but the weeks since he had gotten out of jail had been dispiriting. He was trying to look after his daughter, but job interviews kept stalling when his record came up. Plus, his sentencing judge had earlier said she’d give him 19 years if she saw him again.

Brady was there. She had stepped up efforts to earn her GED because she had been told it would help her get a scholarship at a community college. Hawkins arrived with his son, still trying to find something better than his $7.50-an-hour landscaping gig. His wife was getting out of Jessup soon, but for the time being, “I’m a 24-hour pop!” he said. “It’s nerve -racking. And a lot of brothers can’t do it, and I lost a lot of friends because people would say the stupidest thing to me, like, ‘Why don’t you just give ’em to your mother, and you get out there and get yours?’ ” The answer was simple: “My father wasn’t there for me, and he coulda been. There’s nothing on this earth that could keep me from my son. And to know that everything I do for him and my family makes me a better person. And this program has made me see that there’s another way.”

In July, the ReWired crew gathered again at the Village House for a good-bye of sorts. “Body of Proof” was moving to Los Angeles — and Sohn with it.

The gathering was orchestrated by Koli Tengalla, a veteran community activist and a fellow at the Open Society Institute whom Sohn hired to direct the Village House. The program was always designed to function without her. After she left, however, Hawkins, Brady and others asked for more responsibility and set up a snowball stand to raise funds to pay for GED tutoring for their classmates and school supplies for younger kids.

After leaving prison, Shakiara Hawkins started interning at the Village House and was later hired as a part-time assistant. Sean Hawkins got a better paying job, too, in the warehouse of an event production company run by a man who met Sohn at her favorite Baltimore pub and offered his help. Brady was not only working; she had also enrolled at Baltimore County community college and was on the basketball team. Even Daniels had good news: He was sentenced to 61 days after the judge who said she’d give him 19 years was apparently swayed by his story, his pledge to honor his commitment to the court and his ReWired classmates, several of whom attended the sentencing.

Even with the full schedule in California, and a rash of health issues that plagued her last fall, including a burst blood vessel in her colon that landed her in intensive care, Sohn is working closely with Tengalla to plan the next steps for the Village House, trying to develop a mental health piece for the program and trying to connect people like Hawkins and Brady with services ReWired can’t provide, such as job counseling. She’s also searching out new sources of funding and talking up the program in venues such as panel discussions at Harvard and Attorney General Eric Holder’s “Defending Childhood” task force, chaired by former baseball manager Joe Torre.

In December, soon after getting out of the hospital, she flew to Baltimore to testify at the task force’s first hearing. Her voice shaky, she told her tale of transformation, stressing that she had done it, and that there are many kids in Baltimore and elsewhere who can do it — if they get the right help.

It won’t work every time, but “I know what is possible,” she concluded.