Trump Is Struggling to Run Against a White Guy

The president is having a difficult time deploying his traditional culture-war playbook against Biden.

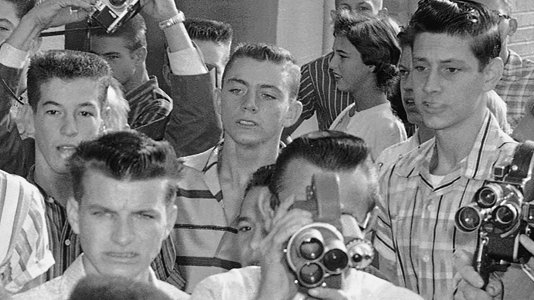

Eight months into Barack Obama’s first term as president, the right-wing radio host Rush Limbaugh, who was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Donald Trump earlier this year, warned that Obama’s election had ushered in a dangerous inversion of power.

“Obama's America—white kids getting beat up on school buses now,” Limbaugh

declared in September 2009, in response to a viral video of a fight between a black teenager and a white teenager on a bus. “In Obama's America, the white kids now get beat up with the black kids cheering.”

Limbaugh was offering a template for the next decade of culture-war arguments on the political right. For eight years, the Republican Party’s chief villain was the first black president, whose center-left liberalism

was decried as “Kenyan anti-colonialism,” whose health-care bill

was “reparations,” and

whose election set off a “race war” waged by power-mad black Americans. His anointed successor, Hillary Clinton—in Limbaugh’s words, a “

feminazi” armed with a “

testicle lockbox”—was an easy target for anxieties about a different inversion of power, that of America’s traditional gender hierarchy. Clinton’s defeat was not sufficient to remove her as a target; to this day, Fox News’s most successful hosts return to the Clinton oasis like wanderers dying of thirst

Trump, first by embracing the “birther” movement, and later as the candidate who promised to return the United States to an idealized past, successfully r

ode these backlashes to the White House. Four years later, Trump is hoping to ride the same wave of anger, fear, and resentment to a second term.

There’s only one problem: His opponent is Joe Biden.

For the past few months, Trump and the conservative propaganda apparatus have struggled to make the old race-and-gender-baiting rhetoric stick to Biden. But voters don’t appear to believe that Biden is an avatar of the “radical left.” They don’t think Biden is going to lock up your manhood in a “testicle lockbox.” They don’t buy that Biden’s platform, which is

well to the left of the ticket he joined in 2008, represents a quiet adherence to “Kenyan anti-colonialism.” Part of this is that Biden has embraced popular liberal positions while avoiding the incentive to adopt more controversial or unpopular positions during the primary. But it’s also becoming clear that after 12 years of feasting on white identity politics with a black man and a woman as its preeminent villains, the Republican Party is struggling to run its Obama-era culture-war playbook against an old, moderate white guy.

The president’s sparsely attended rally in Oklahoma on Saturday was a showcase for Trump’s blunted arsenal. He warned that “the unhinged left-wing mob is trying to vandalize our history, desecrate our beautiful monuments,” to “tear down our statues and punish, cancel, and persecute anyone who does not conform to their demands for absolute and total control.” He warned that the left wants to “defund and dissolve our police departments.” He fantasized about a “tough hombre” breaking into your home at night, warned that Biden was a “puppet of China,” called the coronavirus the “kung flu,” and complained that Democrats had objected to his characterization of some

undocumented immigrants as animals (Trump later claimed he was exclusively referring to MS-13 gang members).

But even Trump didn’t really buy it.

“Joe Biden is a puppet of the radical left,” Trump said, before acknowledging that “he's not radical left. I don't think he knows what he is anymore. But he was never radical left.”

Trump’s supporters are having similar trouble talking themselves into believing Joe Biden is the apocalypse. In 2016, an

unlimited variety of merchandise and swag referring to Hillary Clinton in unprintable sexist terms was available at every Trump rally. In 2020, Trump fans

cannot even come up with Biden T-shirts to sell. Biden has been eating into Trump’s support

among older voters and

even among white evangelicals, a group Biden cannot expect to win but whose support Trump cannot afford to allow to slip. When the Fox News host Laura Ingraham

warns that Biden “will just melt for the macchiato Marxists,” you can sense the weariness of a tired stand-up comic clinging to a set that no longer makes anyone laugh.

I don’t want to overemphasize the importance of campaigns. The unemployment rate is above

13 percent, and may be as high as 16 percent; more than 120,000 Americans have died in a pandemic; and thousands upon thousands have joined protests against police brutality in the past few weeks. A majority of the public believes Trump has botched his response to all three of these events, and as a result

he is polling badly.

Yet none of this means Trump cannot prevail. The first five months of the year have seen a pandemic, an economic collapse, and a nationwide uprising against racism in policing. The next five might yet see a Trump comeback, particularly if the economy recovers before November, if some unforeseen event turns the political landscape to Trump’s advantage, or if Biden himself implodes somehow. But up until this point, the former vice president has proved far more resilient than his detractors have expected, even surviving Trump’s attempt to extort Ukraine into

implicating Biden in a crime that never occurred, an act for which Trump was impeached earlier this year.

Although Democrats may take heart from Republicans’ difficulty in deploying their traditional culture-war playbook against Biden, that very difficulty illustrates how embedded racism and sexism remain in American society. Biden

himself mused last year, “I think there's a lot of sexism in the way they went after Hillary. I think it was unfair. An awful lot of it. Well, that's not gonna happen with me."

Biden’s electability pitch was not just about being moderate relative to the rest of the primary field, but also about being a straight, Christian, white man, one whom Republicans would find difficult to paint as a dire threat to America as conservative white voters understand it. While Biden’s campaign struggled in Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada,

one black voter told The New York Times, “Black voters know white voters better than white voters know themselves. So yeah, we’ll back Biden, because we know who white America will vote for in the general election in a way they may not tell a pollster or the media.” In the primary, Biden’s strength, particularly with

older black voters, seemed to stem not only from his long-term relationships with black leaders or his association with Obama, but from voters’ perception that his background makes him ideally suited to halt Trumpism before it turns into the kind of

decades-long backlash that

followed the civil-rights movement.

Their bet on Biden as the candidate best positioned to neutralize Trump’s white identity politics appears to be paying off for the moment.

Politico reported on Monday that the president is “surprisingly hesitant to engage his opponent—at least by Trump standards—and some advisers think he’s struggling with how to take him on.” It is not just that Trump’s supporters find Biden less threatening because he is a white man; the president himself feels that way. The notion of a Biden presidency simply does not provoke the visceral rage that Clinton and Obama did—not in Trump, and not in his supporters.

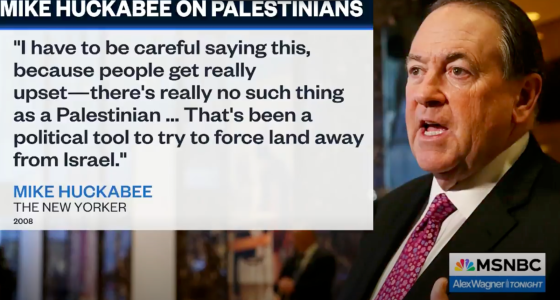

It’s not that Biden, as compared to his predecessors, lacks flaws for Trump to exploit. In fact, while the two candidates are different in most of the ways that really matter—Biden has a baseline respect for democracy and the ability to express remorse—they possess superficial similarities. Watching Republicans struggle to land a punch on an elderly white man with suspicious hair, a reputation

for exaggerations and fibs, questionable

policy judgment, and a track record of

racist remarks who is running a

nostalgic campaign for a bygone era, and yet whom voters seem willing to give the benefit of the doubt no matter what—well let’s just say their opponents know what that’s like.

That Trump’s campaign is being hampered by some of the same social forces he rode to victory in 2016 might be a source of dark amusement. But when you think about it for more than five minutes, it’s not terribly funny.