Correct, Comrade. No one in the history of the world has responded to deadly storms better than Donald J. Trump.Yeah that huge tree that killed a mother and her child when it fell on their house could have happened any other time. Had nothing to do with the hurricane.

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

***Official Political Discussion Thread***

- Thread in 'General' Thread starter Started by rico x hood,

- Start date

- Mar 30, 2007

- 151,175

- 202,618

- Mar 27, 2004

- 18,386

- 34,061

He should remove regular signs as well because no literate person is going to stay at Trump Tower either.

Lose your income to own the Libs.

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/brutal-map-shows-u-s-farmers-want-trump-end-trade-war-123443562.html

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/brutal-map-shows-u-s-farmers-want-trump-end-trade-war-123443562.html

- Dec 15, 2017

- 17,811

- 43,327

Trumpists wanted a businessman as a president?

Welp.

Welp.

- Jun 28, 2004

- 6,971

- 17,045

Military Parades, weird hair, blowing money on military spending, imposing austerity elsewhere, restricting immigration and reducing trade, it's very clear that Donald trump is more than just a president, he is a prophet, he is the great leader who shall usher in an era of self reliance and a liberatory changing of all previous structures. Donald trump is the man who will bring Juche to the United States.

The soy and corn farmers must learn that their needs are subordinated to the nation's need for Jarip, economic self sufficiency. Donald trump is no Russian pawn, Russians abandoned Marxism-Leninism, which itself is inferior compared to Juche.

We must all support and sacrifice for the good of our nation and the success of our dear leader, Don-il Trump.

The soy and corn farmers must learn that their needs are subordinated to the nation's need for Jarip, economic self sufficiency. Donald trump is no Russian pawn, Russians abandoned Marxism-Leninism, which itself is inferior compared to Juche.

We must all support and sacrifice for the good of our nation and the success of our dear leader, Don-il Trump.

- Mar 30, 2007

- 151,175

- 202,618

Nike Jordan

Supporter

- Jun 27, 2002

- 33,938

- 81,201

Boss Hogg really has the NRA shook.

- Mar 30, 2007

- 151,175

- 202,618

- Feb 25, 2010

- 24,952

- 23,299

She was the first lady

Are they going to remove Bill too?

Are they going to remove Bill too?

- Nov 3, 2012

- 16,413

- 8,760

Clickbaity af lmao

- Oct 10, 2013

- 43,425

- 42,998

Well...... they still teach that the pilgrims came to America and were friends with the natives so....... why not?She was the first lady

Are they going to remove Bill too?

aepps20

Supporter

- Feb 8, 2004

- 42,534

- 90,748

Excellent news and a good start. We have to start somewhere fighting against Lib conjecture and innuendo. Hopefully the Obummer years can also be removed.

- Oct 10, 2013

- 43,425

- 42,998

Holocaust and slavery to be removed too soon. We all know they either didn’t happen, weren’t “that bad” and were a choice.

Last edited:

- Jan 12, 2013

- 26,836

- 38,454

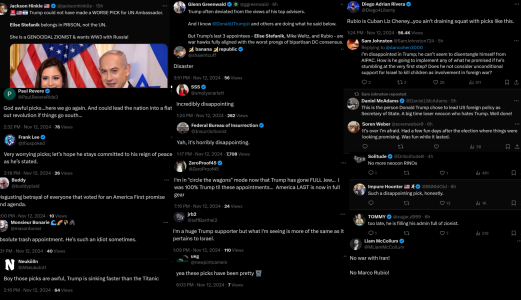

This is the best he could come up with...? Disappointing.

https://www.politico.com/story/2018/09/15/trump-manafort-mueller-plea-deal-825759

President Donald Trump on Saturday fired his first salvo against special counsel Robert Mueller since former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort entered a plea deal with the Russia probe's federal prosecutors.

"While my (our) poll numbers are good, with the Economy being the best ever, if it weren’t for the Rigged Russian Witch Hunt, they would be 25 points higher!" Trump tweeted. "Highly conflicted Bob Mueller & the 17 Angry Democrats are using this Phony issue to hurt us in the Midterms. No Collusion!"

Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani also broke his silence on Manafort's intended guilty plea earlier Saturday, alleging in a tweet that "sources close to" Manafort's defense team told the former New York mayor that the cooperation agreement "does not involve the Trump campaign" and that there was "no collusion with Russia" from within the Trump campaign.

Giuliani added: "Another road travelled by Mueller. Same conclusion: no evidence of collusion President did nothing wrong."

https://www.politico.com/story/2018/09/15/trump-manafort-mueller-plea-deal-825759

President Donald Trump on Saturday fired his first salvo against special counsel Robert Mueller since former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort entered a plea deal with the Russia probe's federal prosecutors.

"While my (our) poll numbers are good, with the Economy being the best ever, if it weren’t for the Rigged Russian Witch Hunt, they would be 25 points higher!" Trump tweeted. "Highly conflicted Bob Mueller & the 17 Angry Democrats are using this Phony issue to hurt us in the Midterms. No Collusion!"

Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani also broke his silence on Manafort's intended guilty plea earlier Saturday, alleging in a tweet that "sources close to" Manafort's defense team told the former New York mayor that the cooperation agreement "does not involve the Trump campaign" and that there was "no collusion with Russia" from within the Trump campaign.

Giuliani added: "Another road travelled by Mueller. Same conclusion: no evidence of collusion President did nothing wrong."

News of Manafort's plea deal came Friday, just days before the longtime GOP operative was due to appear in a Washington, D.C., courtroom to face charges of foreign lobbying and money laundering. Manafort was previously found guilty of eight counts of bank and tax fraud in a separate trial that took place in Virginia last month.

Friday’s plea agreement said Manafort "shall cooperate fully, truthfully, completely and forthrightly with the Government and other law enforcement authorities identified by the Government in any and all matters to which the Government deems the cooperation relevant.”

Trump's tweet Saturday also comes as the president is facing a slate of polls showing his popularity on the downswing weeks away from the midterm elections.

- Mar 30, 2007

- 151,175

- 202,618

- Jan 12, 2013

- 26,836

- 38,454

Trump may be the most divisive president in modern history but to his credit, he did manage to bring the EU, Germany, France, the UK, Russia and China together for something.

Of course he did so by unilaterally withdrawing from the Iran deal against his Defense Secretary's advice and then sabotaging the efforts of all the other signatory states to uphold the Iran deal.

When you think about it, who wouldn't want to collapse the only existing safeguard against Iran's nuclear program? Sure there's Secretary Mattis, the EU, the UK, France, Germany, Russia and China but they haven't sucked up to president Trump enough for their opinion to be validated. They might as well be libbies.

And who even needs a replacement plan when you have the Don in charge?

Especially when you take into account that he is surrounded by level-headed people like John Bolton.

Which brings me to my next point, one that worries me a lot. (see below the article)

https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-...-to-thwart-us-donald-trump-sanctions-on-iran/

Europe looks to thwart Trump’s Iran sanctions

Defiance of Washington will further strain transatlantic ties.

Europe’s biggest economic powers are planning to create a “special purpose” financial company to thwart U.S. President Donald Trump’s sanctions and help Iran to continue to sell oil in the EU.

The move, by France, Germany and Britain, and supported by the EU, is likely to enrage Trump, who in May unilaterally withdrew from the Iran nuclear accord, which the Europeans, Russia and China continue to support and have pledged to do their utmost to protect.

A first battery of renewed U.S. economic sanctions took effect against Iran last month, and further sanctions — including sanctions on the Iranian oil sector, a mainstay of the country’s economy — are set to take hold in November.

Regarding my next point I mentioned earlier, the NYT is reporting that Mattis has fallen out of favor and may be on his way out.

Mattis is just about the only Trump cabinet official who I have full confidence (or any significant confidence really) in. Are there things I disagree with? Sure, but he is in my opinion easily the most qualified and level-headed cabinet member. European diplomats have continued to be very receptive and positive about Mattis as well.

One moment involving Mattis that stuck with me was that on-camera cabinet meeting Trump did pretty early on, where every cabinet member one by one showered Trump with lavish praise. It was like something straight out of a cult gathering.

The one exception was Mattis, who simply dedicated his praise to the troops and the military.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/15/...tion=click&module=Top Stories&pgtype=Homepage

(Lengthy article)

Fraying Ties With Trump Put Jim Mattis’s Fate in Doubt

Back when their relationship was fresh and new, and President Trump still called his defense secretary “Mad Dog” — a nickname Jim Mattis detests — the wiry retired Marine general often took a dinner break to eat burgers with his boss in the White House residence.

Mr. Mattis brought briefing folders with him, aides said, to help explain the military’s shared “ready to fight tonight” strategy with South Korea, and why the North Atlantic Treaty Organization has long been viewed as central to protecting the United States. Using his folksy manner, Mr. Mattis talked the president out of ordering torture against terrorism detainees and persuaded him to send thousands more American troops to Afghanistan — all without igniting the public Twitter castigations that have plagued other national security officials.

But the burger dinners have stopped. Interviews with more than a dozen White House, congressional and current and former Defense Department officials over the past six weeks paint a portrait of a president who has soured on his defense secretary, weary of unfavorable comparisons to Mr. Mattis as the adult in the room, and increasingly concerned that he is a Democrat at heart.

Nearly all of the officials, as well as confidants of Mr. Mattis, spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the internal tensions — in some cases, out of fear of losing their jobs.

In the second year of his presidency, Mr. Trump has largely tuned out his national security aides as he feels more confident as commander in chief, the officials said. Facing what is likely to be a heated re-election fight once the 2018 midterms are over, aides said Mr. Trump was pondering whether he wanted someone running the Pentagon who would be more vocally supportive than Mr. Mattis, who is vehemently protective of the American military against perceptions it could be used for political purposes.

White House officials said Mr. Mattis had balked at a number of Mr. Trump’s requests. That included initially slow-walking the president’s order to ban transgender troops from the military and refusing a White House demand to stop family members from accompanying troops deploying to South Korea. The Pentagon worried that doing so could have been seen by North Korea as a precursor to war.

Of course he did so by unilaterally withdrawing from the Iran deal against his Defense Secretary's advice and then sabotaging the efforts of all the other signatory states to uphold the Iran deal.

When you think about it, who wouldn't want to collapse the only existing safeguard against Iran's nuclear program? Sure there's Secretary Mattis, the EU, the UK, France, Germany, Russia and China but they haven't sucked up to president Trump enough for their opinion to be validated. They might as well be libbies.

And who even needs a replacement plan when you have the Don in charge?

Especially when you take into account that he is surrounded by level-headed people like John Bolton.

Which brings me to my next point, one that worries me a lot. (see below the article)

https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-...-to-thwart-us-donald-trump-sanctions-on-iran/

Europe looks to thwart Trump’s Iran sanctions

Defiance of Washington will further strain transatlantic ties.

Europe’s biggest economic powers are planning to create a “special purpose” financial company to thwart U.S. President Donald Trump’s sanctions and help Iran to continue to sell oil in the EU.

The move, by France, Germany and Britain, and supported by the EU, is likely to enrage Trump, who in May unilaterally withdrew from the Iran nuclear accord, which the Europeans, Russia and China continue to support and have pledged to do their utmost to protect.

A first battery of renewed U.S. economic sanctions took effect against Iran last month, and further sanctions — including sanctions on the Iranian oil sector, a mainstay of the country’s economy — are set to take hold in November.

While the EU has already taken steps to obstruct Trump’s sanctions — including potential penalties against firms that enforce the American sanctions without permission of the European Commission — officials in Europe still fear that the U.S. dominance of the world financial system will block most business with Iran. That would ultimately destroy the nuclear accord, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

Tehran itself has warned the Europeans that they should develop new ways of trading with Iran by early November if they want to preserve that nuclear deal.

U.S. officials and diplomats have warned all businesses and countries around the world to stop doing business with Iran. And the White House reacted furiously to the EU’s announcement last month of an €18 million aid package to Iran for projects in support of sustainable economic and social development.

EU officials on Friday confirmed the plan to create the so-called special purpose vehicle, which was first reported by Spiegel, the German news site.

When asked about this financing model, a spokesperson for the German finance ministry said: “The German government is working together with the EEAS and European Commission, as well as France and the United Kingdom, on maintaining financial payment channels with Iran. The negotiations on this are intensive and ongoing. There are different models under consideration.”

A French official added the EU needs “a financially independent sovereign channel” in order to keep the Iran deal alive.

News of the plan comes only two days after European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker vowed in his final State of the Union address to increase the role of the euro in international trade, particularly in terms of energy purchases.

Word of the European plan to prop up Iran’s oil industry is certain to further damage the already badly strained transatlantic relationship.

Trump’s combative and unilateral approach on numerous policies, including his withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, his trade tariffs, criticisms of NATO, and decision to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, have dismayed America’s most stalwart and long-standing European allies.

One EU official explained that the “special purpose vehicle” would effectively function as an accounting firm, providing a loophole to keep trade flowing between EU countries and Iran. If Italy wants to buy Iranian oil, it could wire money to the firm, which would handle the rest of the transaction. Iran, similarly, could wire money for the purchase of European products.

The special purpose vehicle would keep the money for the transactions within the EU, and outside the reach of U.S. control over global money-transfer systems. It would also avoid the need to use banks that are afraid of being cut off from doing business in the U.S. financial market if they are accused by the U.S. Treasury Department of violating the sanctions.

Crucial decisions are still to be made, the official said, including where the new firm would be established, how its ownership would be structured, and the precise sources and amounts of startup capital.

Regarding my next point I mentioned earlier, the NYT is reporting that Mattis has fallen out of favor and may be on his way out.

Mattis is just about the only Trump cabinet official who I have full confidence (or any significant confidence really) in. Are there things I disagree with? Sure, but he is in my opinion easily the most qualified and level-headed cabinet member. European diplomats have continued to be very receptive and positive about Mattis as well.

One moment involving Mattis that stuck with me was that on-camera cabinet meeting Trump did pretty early on, where every cabinet member one by one showered Trump with lavish praise. It was like something straight out of a cult gathering.

The one exception was Mattis, who simply dedicated his praise to the troops and the military.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/15/...tion=click&module=Top Stories&pgtype=Homepage

(Lengthy article)

Fraying Ties With Trump Put Jim Mattis’s Fate in Doubt

Back when their relationship was fresh and new, and President Trump still called his defense secretary “Mad Dog” — a nickname Jim Mattis detests — the wiry retired Marine general often took a dinner break to eat burgers with his boss in the White House residence.

Mr. Mattis brought briefing folders with him, aides said, to help explain the military’s shared “ready to fight tonight” strategy with South Korea, and why the North Atlantic Treaty Organization has long been viewed as central to protecting the United States. Using his folksy manner, Mr. Mattis talked the president out of ordering torture against terrorism detainees and persuaded him to send thousands more American troops to Afghanistan — all without igniting the public Twitter castigations that have plagued other national security officials.

But the burger dinners have stopped. Interviews with more than a dozen White House, congressional and current and former Defense Department officials over the past six weeks paint a portrait of a president who has soured on his defense secretary, weary of unfavorable comparisons to Mr. Mattis as the adult in the room, and increasingly concerned that he is a Democrat at heart.

Nearly all of the officials, as well as confidants of Mr. Mattis, spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the internal tensions — in some cases, out of fear of losing their jobs.

In the second year of his presidency, Mr. Trump has largely tuned out his national security aides as he feels more confident as commander in chief, the officials said. Facing what is likely to be a heated re-election fight once the 2018 midterms are over, aides said Mr. Trump was pondering whether he wanted someone running the Pentagon who would be more vocally supportive than Mr. Mattis, who is vehemently protective of the American military against perceptions it could be used for political purposes.

White House officials said Mr. Mattis had balked at a number of Mr. Trump’s requests. That included initially slow-walking the president’s order to ban transgender troops from the military and refusing a White House demand to stop family members from accompanying troops deploying to South Korea. The Pentagon worried that doing so could have been seen by North Korea as a precursor to war.

Over the last four months alone, the president and the defense chief have found themselves at odds over NATO policy, whether to resume large-scale military exercises with South Korea and, privately, whether Mr. Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the Iran nuclear deal has proved effective.

The arrival at the White House earlier this year of Mira Ricardel, a deputy national security adviser with a history of bad blood with Mr. Mattis, has coincided with new assertions from the West Wing that the defense secretary may be asked to leave after the midterms.

Mr. Mattis himself is becoming weary, some aides said, of the amount of time spent pushing back against what Defense Department officials think are capricious whims of an erratic president.

The defense secretary has been careful to not criticize Mr. Trump outright. Pentagon officials said Mr. Mattis had bent over backward to appear loyal, only to be contradicted by positions the president later staked out. How much longer Mr. Mattis can continue to play the loyal Marine has become an open question in the Pentagon’s E Ring, home to the Defense Department’s top officials.

The fate of Mr. Mattis is important because he is widely viewed — by foreign allies and adversaries but also by the traditional national security establishment in the United States — as the cabinet official standing between a mercurial president and global tumult.

“Secretary Mattis is probably one of the most qualified individuals to hold that job,” Senator Jack Reed of Rhode Island, the top Democrat on the Senate Armed Services Committee, said in an interview. His departure from the Pentagon, Mr. Reed said, “would, first of all, create a disruption in an area where there has been competence and continuity.”

But that very sentiment is part of a narrative the president has come to resent.

The one-two punch last week of the Bob Woodward book that quoted Mr. Mattis likening Mr. Trump’s intellect to that of a “fifth or sixth grader,” combined with the New York Times Op-Ed by an unnamed senior administration official who criticized the president, has fueled Mr. Trump’s belief that he wants only like-minded loyalists around him. (Mr. Mattis has denied comparing his boss to an elementary school student and said he did not write the Op-Ed.)

Mr. Trump, two aides said, wants Mr. Mattis to be more like Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, a political supporter of the president. During a televised June 21 cabinet meeting, held as migrant children were being separated from their parents at the southwestern border, Mr. Mattis and Mr. Pompeo were a study of contrasts: On the president’s left, the defense secretary sat stone-faced; on his right, the secretary of state was chuckling at all of Mr. Trump’s jokes.

Getting Mr. Mattis to abandon the apolitical stand he has clung to his entire life will be next to impossible, his friends and aides said.

Mr. Mattis has assiduously avoided the limelight during his tenure because he is fearful, aides said, about being put on the spot by questions that will expose differences with his boss. He has batted down multiple requests from the White House to go on “Fox & Friends” to praise the president’s agenda. And he has appeared before reporters at the podium in the Pentagon press room only a handful of times, giving remarkably few on-the-record one-on-one news media interviews — one of which was with a reporter for a high school newspaper in Washington State who had obtained Mr. Mattis’s cellphone number.

“Secretary Mattis lives by a code that is part of his DNA,” said Capt. Jeff Davis, who retired last month from the Navy after serving as a spokesman for Mr. Mattis since early in the Trump administration. “He is genetically incapable of lying, and genetically incapable of disloyalty.”

That means the defense secretary’s only recourse is to stay silent, aides to Mr. Mattis said. While he does not want to publicly disagree with his boss, he is also uncomfortable with showering false praise on Mr. Trump.

But cracks are showing.

In April, John R. Bolton became the White House national security adviser, replacing Army Lt. Gen. H. R. McMaster, who was long viewed as a subordinate to Mr. Mattis because of his rank as a three-star general compared with the retired Marine general’s four stars. Mr. Bolton is far more hawkish than either Mr. Mattis or General McMaster; administration officials said his deputy, Ms. Ricardel, actively dislikes the Pentagon chief — a feeling Mr. Mattis is believed to return in full.

Ms. Ricardel, a former Boeing executive who worked at the Pentagon during the George W. Bush administration, has a reputation for being as combative as Mr. Bolton.

As the Trump transition official responsible for Pentagon appointments, Ms. Ricardel stopped Mr. Mattis from hiring Anne Patterson as under secretary of defense for policy, one of the department’s highest political jobs. Ms. Patterson was a career diplomat who served as an ambassador under Presidents Bush, Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, but administration officials said Ms. Ricardel suspected Mr. Mattis was trying to load up the Pentagon with Democrats and former supporters of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

(Mr. Mattis also tried, unsuccessfully, to hire Michèle A. Flournoy, a Defense Department under secretary in the Obama administration, as his deputy. “He needed a deputy who wouldn’t be struggling every other day about whether they could be part of some of the policies that were likely to take shape,” Ms. Flournoy told a conference hosted by Politico.)

After a stint at the Commerce Department, Ms. Ricardel moved to the White House as Mr. Bolton’s deputy. Since her arrival, friction has increased between the White House and the Pentagon — along with speculation from West Wing aides that Mr. Mattis’s star is falling.

For instance, Mr. Mattis has recently resisted White House attempts to closely supervise military operations by demanding details about American troops involved in specific raids in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

One American official said the White House had bypassed the Pentagon by getting classified briefings of coming operations directly from the Special Operations task forces, to the frustration of Mr. Mattis.

That may seem a small and insular example of bureaucratic gamesmanship. But administration officials said it illustrates the tensions between Mr. Mattis and Mr. Trump: Either the defense secretary cannot appeal to the president, or he has and Mr. Trump is refusing to back him up.

Asked about disagreements between the National Security Council and the Pentagon, Garrett Marquis, a council spokesman, said in an email that “Ambassador Bolton is coordinating and working closely with all national security agencies to provide the president with national security options and guidance.”

In contrast with General McMaster, Mr. Bolton recently began attending regular weekly meetings between Mr. Mattis and Mr. Pompeo. Pentagon officials complain that White House interference has returned to the level of Susan E. Rice, who as Mr. Obama’s national security adviser was accused of micromanaging the department’s every move.

Mr. Mattis has repeatedly been blindsided by his boss this summer.

In June, Mr. Trump ordered Mr. Mattis to set up a Space Force over the defense secretary’s objections that such a move would weigh down an already cumbersome bureaucracy.

In July, the president blew up a NATO summit meeting that Mr. Mattis and other national security officials had worked on for months. The Pentagon chief and others saved the final agreement only because they shielded it from the president and urged envoys to complete it before Mr. Trump arrived in Brussels.

In August, the president undercut Mr. Mattis after a news conference at the Pentagon in which the defense secretary suggested that the United States military would resume war games on the Korean Peninsula. The exercises had been suspended — against Mr. Mattis’s advice — after Mr. Trump met with the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, in Singapore. “There is no reason at this time to be spending large amounts of money on joint U.S.-South Korea war games,” the president tweeted.

Meanwhile, Mr. Mattis has begun questioning the efficacy of Mr. Trump’s decision to pull out of the Iran nuclear deal — a move that, again, was made against his advice. Mr. Mattis has told aides that he has yet to see any difference in Iran’s behavior since Mr. Trump withdrew the United States from the agreement between world powers and Tehran.

Mr. Mattis famously was pushed out of his job as head of United States Central Command in 2013 because he was viewed as too much of a hawk on Iran policy during the Obama administration. But now, in the Trump administration, Mr. Mattis makes his arguments on Iran from the left of Mr. Bolton, Ms. Ricardel and the president himself.

For Mr. Trump, getting rid of his popular defense secretary would carry a political cost. Mr. Mattis is revered by the men and women of the American military. Most of the rest of his fans are people Mr. Trump does not care about: Democrats, establishment Republicans and American allies.

But moderate Republicans — whom Mr. Trump will need in 2020 — appear to trust Mr. Mattis as well, and firing him could hurt the president with that key group.

Mr. Trump, at the moment, is publicly standing by his defense secretary. “He’ll stay right there,” the president told reporters last week when asked about Mr. Mattis’s comments in Mr. Woodward’s book. “We’re very happy with him. We’re having victories people don’t even know about.”

As for Mr. Mattis, “there’s no daylight between the secretary and the president when it comes to the unwavering support of our military,” said Dana W. White, the Pentagon press secretary. “It’s up to the president of the United States to decide what he wants to do.”

- Mar 30, 2007

- 151,175

- 202,618

Nike Jordan

Supporter

- Jun 27, 2002

- 33,938

- 81,201

- Jan 12, 2013

- 26,836

- 38,454

Raphael can't even stand up for his own family, let alone his constituents

"Welcoming the help" of the man who claimed your father conspired to kill JFK

- Oct 10, 2013

- 43,425

- 42,998

- Jan 8, 2013

- 2,650

- 4,473

I really hope this FEMA thing that lets the President alert people directly on their phones about emergencies isn't misused to GOTV for Republicans in the midterms.

The Democrats wouldn't be able to do anything until after the elections, and Republicans are obviously going to look the other way, like with everything else.

The Democrats wouldn't be able to do anything until after the elections, and Republicans are obviously going to look the other way, like with everything else.

- Jul 19, 2012

- 23,023

- 33,725

I really hope this FEMA thing that lets the President alert people directly on their phones about emergencies isn't misused to GOTV for Republicans in the midterms.

The Democrats wouldn't be able to do anything until after the elections, and Republicans are obviously going to look the other way, like with everything else.

If it comes in text form I'm blocking the sender immediately.

He's so unlikeable that people in other states want him gone. Instead of self-reflecting, the natural Republican reaction is to blame everyone else.“We’ve got a race on our hands,” Cruz said. “If you're a wealthy liberal sitting in New York City or Massachusetts or San Francisco right now and you could defeat one Republican in the country, it'd be me, that's why the money is flowing in here.”

- Nov 3, 2012

- 16,413

- 8,760

-opens phone-

FROM FEMA:

FROM FEMA:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 45

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 9K

- Views

- 552K

- Replies

- 14K

- Views

- 357K