The Trump administration, in a significant escalation of its clash with the government’s top ethics watchdog, has moved to block an effort to disclose any ethics waivers granted to former lobbyists who now work in the White House or federal agencies.

The latest conflict came in recent days when the White House, in a highly unusual move, sent a letter to Walter M. Shaub Jr., the head of the Office of Government Ethics, asking him to withdraw a request he had sent to every federal agency for copies of the waivers. In the letter, the administration challenged his legal authority to demand the information.

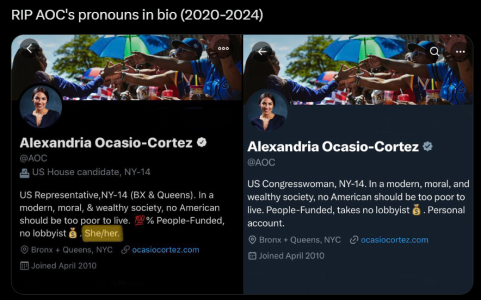

Dozens of former lobbyists and industry lawyers are working in the Trump administration, which has hired them at a much higher rate than the previous administration. Keeping the waivers confidential would make it impossible to know whether any such officials are violating federal ethics rules or have been given a pass to ignore them.

Mr. Shaub, who is in the final year of a five-year term after being appointed by President Barack Obama, said he had no intention of backing down. “It is an extraordinary thing,” Mr. Shaub said of the White House request. “I have never seen anything like it.”

Marilyn L. Glynn, who served as general counsel and acting director of the agency during the George W. Bush administration, called the move by the Trump White House “unprecedented and extremely troubling.”

“It challenges the very authority of the director of the agency and his ability to carry out the functions of the office,” she said.

In a statement issued Sunday evening, the Office of Management and Budget rejected the criticism and instead blamed Mr. Shaub, saying his call for the information, issued in late April, was motivated by politics. The office said it remained committed to upholding ethical standards in the federal government.

“This request, in both its expansive scope and breathless timetable, demanded that we seek further legal guidance,” the statement said. “The very fact that this internal discussion was leaked implies that the data being sought is not being collected to satisfy our mutual high standard of ethics.”

President Trump signed an

executive order in late January — echoing

language first endorsed by Mr. Obama — that prohibited lobbyists and lawyers hired as political appointees from working for two years on “particular” government matters that involved their former clients. In the case of former lobbyists, they could not work on the same regulatory issues they had been involved in.

Both Mr. Trump and Mr. Obama reserved the right to issue waivers to this ban. Mr. Obama, unlike Mr. Trump, automatically made any such waivers public, offering detailed explanations. The exceptions were typically granted for people with special skills, or when the overlap between the new federal work and a prior job was minor.

Ms. Glynn, who worked in the office of government ethics for nearly two decades, said she had never heard of a move by any previous White House to block a request like Mr. Shaub’s. She recalled how the Bush White House had intervened with a federal agency during her tenure to get information that she needed.

Ethics watchdogs, as well as Democrats in Congress, have expressed concern at the number of former lobbyists taking high-ranking political jobs in the Trump administration. In many cases, they appear to be

working on the exact topics they had previously handled on behalf of private-sector clients — including oil and gas companies and Wall Street banks — as recently as January.

Mr. Shaub, in an effort to find out just how widespread such waivers have become, asked every federal agency and the White House to give him a copy by June 1 of every waiver it had issued. He intends to make the documents public.

Federal law gives the Office of Government Ethics, which was

created in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal,

clear legal authority to issue such a “data request” to the ethics officers at federal agencies. This is the main power the office has to oversee compliance with federal ethics standards.

It is less clear whether it has the power to demand such information from the White House. Historically, there has been some debate over whether the White House is a “federal agency” or, as it calls itself, the “executive office of the president.” Such an office might not be subject to oversight.

The White House, however, tried on Wednesday to stop the process across the entire federal government, even before most agencies had responded to Mr. Shaub’s

April 28 request.

“This data call appears to raise legal questions regarding the scope of O.G.E.’s authorities,” said the letter, which was sent to Mr. Shaub by Mick Mulvaney, the head of the Office of Management and Budget. It continued, “I therefore request that you stay the data call until these questions are resolved.”

The letter, which was obtained by The New York Times after a Freedom of Information request, created confusion among federal agency heads about whether they should honor the request from the ethics office.

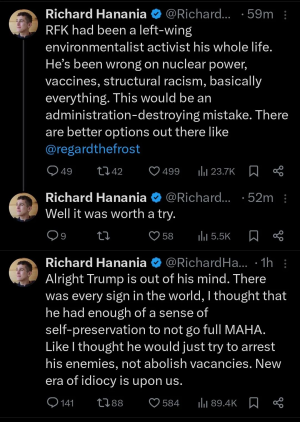

Norman Eisen, the top White House ethics lawyer in the first years of the Obama administration, said he believed that the Trump administration was trying to intimidate federal ethics officers, who are career appointees, without actually ordering them to ignore the directive from the ethics chief.

“It is yet another demonstration of disrespect for the rule of law and for ethics and transparency coming from the White House,” Mr. Eisen said.

Mr. Shaub, in a conference call with federal government ethics officers on Thursday, told them that he had the clear authority to make such a request and that they were still obligated under federal law to provide the requested information, according to a federal official who participated in the call.

The Office of Government Ethics, however, does not have the power to take enforcement action directly against the agencies if they do not respond. Traditionally, if it has trouble getting the information it needs, it turns to the White House to get compliance, Ms. Glynn said.

“The agency is more or less dependent on the good graces of the party that is in power,” she said.

Tensions between Mr. Trump and Mr. Shaub first started to grow in late November, when the Office of Government Ethics sent out an unusual series of Twitter messages urging Mr. Trump to limit potential conflicts of interest by selling off his real estate assets. Mr. Shaub then gave a

speech in January, after Mr. Trump announced that he would not take such a step, which was highly critical of the incoming president, provoking speculation that Mr. Shaub might be fired before his term ended.

“One of the things that make America truly great is its system for preventing public corruption,” Mr. Shaub said

during that speech. “Our executive branch ethics program is considered the gold standard internationally and has served as a model for the world. But that program starts with the office of the president. The president-elect must show those in government — and those coming into government after his inauguration — that ethics matters.”