Our ugly racism’s newest artifact: The noose left at the African American Museum

On Wednesday, as yellow buses disgorged flocks of school groups and multigenerational visitors pushed wheelchairs and strollers into the Smithsonian’s compelling new Museum of African American History and Culture, something entered the building with them:

Hatred.

Sometime in the afternoon, in the gallery on segregation, someone placed the vile instrument of our country’s history of lynching — a noose — inside the museum. It was the second time this week one was found on Smithsonian grounds. A noose was found hanging from a tree near the Hirshhorn museum four days earlier.

But a noose inside the African American History museum was a disturbing reminder that our history of racial oppression and violence is far from over.

“The noose has long represented a deplorable act of cowardice and depravity — a symbol of extreme violence for African Americans,” Lonnie Bunch, the founding director of the museum, said in a statement. “Today’s incident is a painful reminder of the challenges that African Americans continue to face.

“This was a horrible act,” he said, “but a stark reminder of why our work is so important.”

And that’s especially true in Trump’s America, where strident white nationalism is on the rise. The Southern Poverty Law Center has recorded about 1,300 incidents since the 2016 election. They are happening almost every day, all over the country.

Three people have been stabbed to death in the past two weeks by alleged white supremacists –

two men defending a Muslim woman on a train in Portland, Ore., and

Richard W. Collins III, a Bowie State University student out with friends on the University of Maryland College Park campus.

In Los Angeles on Wednesday, someone spray-painted racist graffiti outside the home of

basketball star LeBron James as he prepared for the NBA Finals.

“No matter how much money you have, no matter how famous you are, no matter how many people admire you, being black in America is tough,” James told reporters. And he invoked the memory of Emmett Till’s mother, who forced the world to look at her lynched 14-year-old son. “The reason she had an open casket was that she wanted to show the world what her son went through as far as a hate crime, and being black in America,” James said.

Till’s casket is on display at the African American Museum, where the noose was left on the very same day.

Assuming it was left by a racist, white person, it shouldn’t be too hard to find the suspect. Far too few white people go there.

When the museum opened in September amid the ugly rhetoric of the Trump presidential campaign, I begged my fellow white Americans to please go to the museum.

Because this place isn’t just black history. It’s America’s history.

And the searing, soaring five-story museum fills the gaps in our country’s complicated story that too many of us have forgotten, sanitized or simply never knew.

But white folks weren’t listening too well.

The Smithsonian doesn’t keep formal track of the race of the more than 1 million visitors who have flocked to the museum since it opened. But I could see it every time I passed the building and during my four trips inside. The vast majority of visitors are black.

The very crowd with the most to learn, the Americans wrestling hardest with the legacy of race in their country, seemed to be avoiding the place.

I went to the museum Wednesday to see if my impression was correct.

And with each wave of visitors holding their timed-entry passes, except for the school groups, it was always the same. Black, black, black, black, white, white, black, black, black, black.

“I don’t want to get you in trouble, but you’re here every day,” I said to one security guard. “Would you say this is the demographic profile you see every day?”

“Yes. I’d say about 10 percent. 20 percent white,” the guard said.

Same answer from all of the other employees who were kind enough to talk to me.

Marcia Lawrence and her friend, Mike Goulet, were among the white visitors in the 10:30 a.m. wave. They came from Connecticut, and Lawrence’s daughter, a history teacher in Pennsylvania, got their passes ahead of time.

“We’re all together in this, we’re all one country and we should learn about our country that way,” she said.

There were also plenty of white folks who were thwarted by the museum’s popularity.

“We’re here from Memphis, and we really want to go,” one white couple told me. “But we just didn’t get passes today.”

It’s still a hot ticket. And to get in, you’ve got to go online to get free, timed-entry passes, or get lucky enough to score the walk-up passes released throughout the day.

Not surprisingly, black tourists are more purposeful about coming to the museum. They reserve the passes online, then build a trip around them.

The Morwood family, visiting from San Diego, got lucky with walk-up, day passes on Wednesday.

When they left the museum before lunch Wednesday and blinked in the bright sun outside, they were trying to digest what they had just seen.

“It’s just, why isn’t this in all other museums?” Jenna Morwood, 43, asked. “I mean, when you see the impact, the rich history and you see what was left out of all these other museums across the country, you wonder. And you realize how white-centric we are.”

She got it.

And so did the eighth graders in watermelon-pink school shirts from De Kalb, Tex.

“What really got me was how many people didn’t survive the trip over,” said Maebry Petty, 13, shaking her head a bit. “Those slave ships.”

The millions brought in chains to the United States also stunned her dad, Ray Petty, 37, who’d never been to Washington and was now so glad he’d chaperoned this trip.

One of the other teens in their group said that learning this history “was like learning about the Holocaust. We have to.”

We have to.

The waves of middle schoolers gave me hope. They are learning far more about our nation’s truth than their parents and grandparents did.

But when that noose was found just a few hours later, I couldn’t believe it.

Someone walked inside the museum and ignored the power and meaning of the child-size shackles, the human bill of sale, Emmett Till’s casket and the gruesome photos of lynchings. A noose placed alongside these artifacts yanked us back into that past, reminding us that the most virulent strains of racism are still with us.

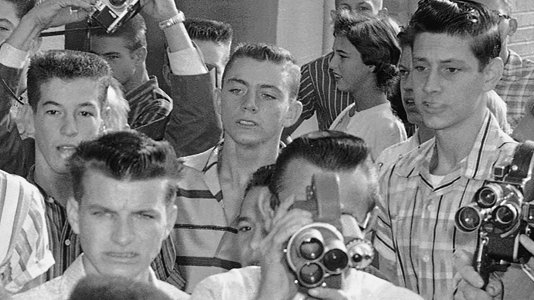

“We haven’t seen such mainstream support for hate in decades, not since the civil rights era 50 years ago,” Southern Poverty Law Center spokesman Ryan Lenz told

Smithsonian magazine.

Police cordoned off the section where the noose was found and removed it as evidence.

When the investigation is over, they should bring it back. Leave it right where they found it. And the museum can put it in a glass case, with a marker noting: “Noose. Symbol of contemporary hatred and racism. 2017.”

This isn’t history yet.