Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

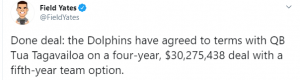

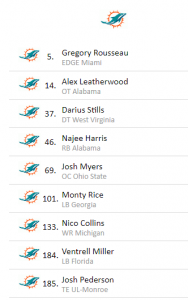

OFFICIAL 2021 MIAMI DOLPHINS OFFSEASON THREAD: AND WITH THE 3RD PICK OF THE........

- Thread in 'Sports & Training' Thread starter Started by h3at23,

- Start date

D

Deleted member 37754

Guest

D

Deleted member 37754

Guest

- Mar 26, 2009

- 7,679

- 377

@AlbertBreer

Full terms of Texans/Dolphins trade, per source ... Dolphins get: 2020 first-round pick, 2021 first-round pick, 2021 second-round pick, CB Johnson Bademosi, OT Julie'n Davenport. Texans get: OT Laremy Tunsil, WR Kenny Stills, 2020 fourth-round pick, 2021 sixth-round pick.

I did NOT want to see Tunsil and/or Kenny go but that haul my GOD!

D

Deleted member 37754

Guest

It’s been a crazy offseason.

Kiko is still on the roster but you can bet he will be traded at some point. They have no seeming interest in using him, I would take a solid 4th/5th rounder for him and call it a day. Guess you could say the same about Jones but I don’t think anyone is touching that dumb contract.

The next two years should be from with free agency and the draft. The defense will be fun to watch, the offense will probably be a train wreck. Be interesting to see who develops and who doesn’t.

Kiko is still on the roster but you can bet he will be traded at some point. They have no seeming interest in using him, I would take a solid 4th/5th rounder for him and call it a day. Guess you could say the same about Jones but I don’t think anyone is touching that dumb contract.

The next two years should be from with free agency and the draft. The defense will be fun to watch, the offense will probably be a train wreck. Be interesting to see who develops and who doesn’t.

- Jul 3, 2018

- 11,415

- 21,302

Helluva haul.

D

Deleted member 37754

Guest

Kiko gone.

Traded to the Saints.

Edit: no picks, for a LB

Vince Biegel

Dolphins just loading up on Wisconsin players.

Traded to the Saints.

Edit: no picks, for a LB

Vince Biegel

Dolphins just loading up on Wisconsin players.

Last edited by a moderator:

2019 1st (Likely Top 3)

2019 1st (Hou)

2019 2nd

2019 2nd (NO)

2019 3rd

2019 3rd (James Comp)

2019 4th (Tenn)

2019 5th (Wake Comp)

2019 6th

2019 6th (Dal)

2019 7th

2019 7th (KC)

2020 1st (Likely Top 5-7)

2020 1st (Hou)

2020 2nd

2020 2nd (Hou)

2020 3rd

2020 4th

2020 5th

2020 7th

All this, and well over 100+ mil in cap space.

Since I have been on this board, I have asked for a complete and utter tear down/rebuild. It's FINALLY here.

Note, we can still flip Reshad for something.

We could flip Drake.

We can flip Rosen.

And if we really wanna get crazy, we could trade Howard. He could net us another 2-3 premium picks. If we trade all these pieces, we could have 25-30 picks in two years.

2019 1st (Hou)

2019 2nd

2019 2nd (NO)

2019 3rd

2019 3rd (James Comp)

2019 4th (Tenn)

2019 5th (Wake Comp)

2019 6th

2019 6th (Dal)

2019 7th

2019 7th (KC)

2020 1st (Likely Top 5-7)

2020 1st (Hou)

2020 2nd

2020 2nd (Hou)

2020 3rd

2020 4th

2020 5th

2020 7th

All this, and well over 100+ mil in cap space.

Since I have been on this board, I have asked for a complete and utter tear down/rebuild. It's FINALLY here.

Note, we can still flip Reshad for something.

We could flip Drake.

We can flip Rosen.

And if we really wanna get crazy, we could trade Howard. He could net us another 2-3 premium picks. If we trade all these pieces, we could have 25-30 picks in two years.

Last edited:

Every time the Texans lose, we win this season. They have a tough schedule, possible they get to 8-8/9-7 type season, giving us a Top 15ish pick? If they get to 10-11 wins, they obviously give us only a mid 20's pick like 25 or somethin, but if they stumble at all.....the value of that pick (and they wouldn't be improving much for 2021's draft picks either) could be HUGE for us. Need Jax, Indy, and Tenn to at least take one each. If they do that, suddenly 6-10 is doable and that's a Top 10-12 pick range.

2020 1st (Likely Top 3)

2020 1st (Pitt)

2020 1st (Hou)

2020 2nd

2020 2nd (NO)

2020 3rd

2020 3rd (James Comp)

2020 5th (Pitt)

2020 5th (Wake Comp)

2020 6th

2020 6th (Dal)

2020 7th

2020 7th (KC)

2021 1st (Likely Top 5-7)

2021 1st (Hou)

2021 2nd

2021 2nd (Hou)

2021 3rd

2021 4th

2021 5th

2021 6th (Pitt)

All this, and well over 150+ mil in cap space.

Since I have been on this board, I have asked for a complete and utter tear down/rebuild. It's FINALLY here.

Note, we can still flip Reshad for something.

We could flip Drake.

We can flip Rosen.

And if we really wanna get crazy, we could trade Howard. He could net us another 2-3 premium picks. If we trade all these pieces, we could have 25-30 picks in two years.

We just got the Steelers 1st after they lost Ben for the year and are already 0-2.

Last edited:

Somethin I typed up in WIR thread. Just how I'm thinkin on 9/23.......

I'm nobody, but let me take a stab on Sept 23rd.

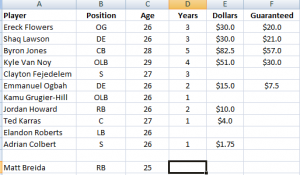

150+ mil in cash. I know I have to overpay a little, so maybe I go half and half. O and D

I'll sign OT Andrus Peat, and OG Joe Thuney

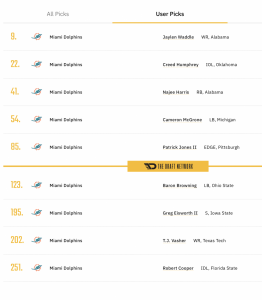

Draft Tua

Two other firsts, gimme OT Tristan Wirfs and OC Tyler Biadsz.

I still have money of course, maybe I can get Melvin Gordon and Amari Cooper. (I work on the assumption Dallas has paid everyone else, they can't afford Cooper and as I said, we can overpay a little)

Speaking of that, I also would like to buy Byron Jones (Same as Coop, Dallas pays Dak and we get a couple pieces. And maybe Vonn Bell.

Two second round picks, I go DE with both. Maybe something like Weaver and Okwara.

Two thirds, 4-7 etc etc fill in and hope 1-2 stick somewhere.

That's signing 2 OL, 1 RB lookin to get paid, 1 WR lookin to get paid, 1 CB, and 1 S.

Tua + 2 OL + 2 DE in the first two rounds of the draft.

Is that "doable"? Is that pipe dreaming? No way we can sign 6 players (6 KEY players, likely there will be plenty of random buys, these are just the key pieces you attempt to fill with)

I like Scherff, but see he's getting offers already, and I thought about AJ Green, but his age/injuries concern me, Derrick Henry could be in play, maybe Artie Burns? So there's options to my choices, but these seem to be a fairly reasonable ask. I may not get all 6, but could take one of these lesser guys, like Burns instead of Byron, or Henry instead of Gordon, etc.

And of course, we will still have two firsts and two seconds next year to keep adding either more weapons, or maybe more beef at LB, or S, or OL, or DL, WR, etc etc etc.

It's too early to tell right now, but it is possible to have an OLine for Tua right away. Problem is, we have to prioritize it. God help me if they don't. I will be furious.

I'm nobody, but let me take a stab on Sept 23rd.

150+ mil in cash. I know I have to overpay a little, so maybe I go half and half. O and D

I'll sign OT Andrus Peat, and OG Joe Thuney

Draft Tua

Two other firsts, gimme OT Tristan Wirfs and OC Tyler Biadsz.

I still have money of course, maybe I can get Melvin Gordon and Amari Cooper. (I work on the assumption Dallas has paid everyone else, they can't afford Cooper and as I said, we can overpay a little)

Speaking of that, I also would like to buy Byron Jones (Same as Coop, Dallas pays Dak and we get a couple pieces. And maybe Vonn Bell.

Two second round picks, I go DE with both. Maybe something like Weaver and Okwara.

Two thirds, 4-7 etc etc fill in and hope 1-2 stick somewhere.

That's signing 2 OL, 1 RB lookin to get paid, 1 WR lookin to get paid, 1 CB, and 1 S.

Tua + 2 OL + 2 DE in the first two rounds of the draft.

Is that "doable"? Is that pipe dreaming? No way we can sign 6 players (6 KEY players, likely there will be plenty of random buys, these are just the key pieces you attempt to fill with)

I like Scherff, but see he's getting offers already, and I thought about AJ Green, but his age/injuries concern me, Derrick Henry could be in play, maybe Artie Burns? So there's options to my choices, but these seem to be a fairly reasonable ask. I may not get all 6, but could take one of these lesser guys, like Burns instead of Byron, or Henry instead of Gordon, etc.

And of course, we will still have two firsts and two seconds next year to keep adding either more weapons, or maybe more beef at LB, or S, or OL, or DL, WR, etc etc etc.

It's too early to tell right now, but it is possible to have an OLine for Tua right away. Problem is, we have to prioritize it. God help me if they don't. I will be furious.

do work son

Banned

- May 22, 2010

- 17,118

- 5,186

Every time the Texans lose, we win this season. They have a tough schedule, possible they get to 8-8/9-7 type season, giving us a Top 15ish pick? If they get to 10-11 wins, they obviously give us only a mid 20's pick like 25 or somethin, but if they stumble at all.....the value of that pick (and they wouldn't be improving much for 2021's draft picks either) could be HUGE for us. Need Jax, Indy, and Tenn to at least take one each. If they do that, suddenly 6-10 is doable and that's a Top 10-12 pick range.

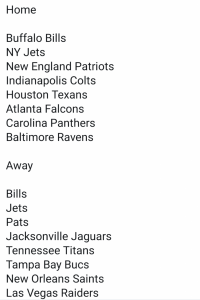

we'll split with indy, sweep Jacksonville and Tennessee. that's 5 wins to put us at 7. I think we'll win 3 of 5 out of carolina denver oakland atlanta tampa . that's 10. we'll lose to KC and NE, but I think Baltimore is a winnable game. that's 11 imo.

we'll split with indy, sweep Jacksonville and Tennessee. that's 5 wins to put us at 7. I think we'll win 3 of 5 out of carolina denver oakland atlanta tampa . that's 10. we'll lose to KC and NE, but I think Baltimore is a winnable game. that's 11 imo.

Well, that sucks. The Chargers let me down big time. I really could have used that game in hand. But 10-11 isn't crazy at all. I was moreso hoping if the wheels fell off type of season.

Thankfully, the Steelers pick is more important now, so I have that to enjoy and the Houston pick isn't as key for us until the 2021 pick is conveyed.

D

Deleted member 37754

Guest

Honestly don’t know what will happen with this Washington game.

Jets are a train wreck but Gase always seems to find himself 8-8, think they will be fine.

Steeers should beat the Phins.

Bengals might be healthy by the time the Dolphins play them. If the Dolphins won a game, would be on of these and Washington. Does make me nervous, would be the Dolphins thing to do, accidentally win games that puts them out of the 1st overall and miss drafting Tua.

Would be great if things just went to plan.

Jets are a train wreck but Gase always seems to find himself 8-8, think they will be fine.

Steeers should beat the Phins.

Bengals might be healthy by the time the Dolphins play them. If the Dolphins won a game, would be on of these and Washington. Does make me nervous, would be the Dolphins thing to do, accidentally win games that puts them out of the 1st overall and miss drafting Tua.

Would be great if things just went to plan.

The Dolphins traded a couple of their star players, Laremy Tunsil and Minkah Fitzpatrick, for future draft picks, and have lost games handily in the first month of the season. Thus the narrative of their “tanking” in 2019, intentionally losing games presumably to be in position to draft Tua Tuagolova or Justin Herbert or whoever will lead them to a special place. What's unsaid is that they are now being quarterbacked by one of those formerly much-hyped prospects, Josh Rosen who—according to the tanking narrative—is merely keeping the seat warm for someone a year or two younger than he is.

Let’s examine what exactly this “tanking” philosophy is and whether it makes organizational sense. I believe we definitely need a better word for this philosophy. And I know just the word:

“Processing”

Tanking implies that the entire organization embraces losing on purpose. Of course, that is not true. Players are still blocking, tackling, running; coaches are still working on game plans and schemes. So let’s be clear: This concept clearly does not apply to the active participants. Where the line becomes much less clear is with the management, although it is a philosophy long used in business and even sports.

Businesses regularly sacrifice short-term success for a more stable long-term future. Jeff Bezos has said that if Amazon has a good quarter (it has had a few), it is because of work and decision-making done three to five years ago. This certainly applies to sports. Successful teams in 2019 formed their roots in 2015-2018.

Unbeknownst to me, I was neighbors with former Philadelphia 76ers general manager Sam Hinkie for several years. When I saw him at a conference a few years ago—we had never met—he came right up to me and said: “You’re fast!” “Excuse me?” “We lived down the street from you; I used to see you run by our house all the time. You're fast!” I’ll take it.

I have talked to Hinkie about the philosophy he brought to the NBA. He had learned through research and analysis that playing on the fringes of the playoffs amounted to being on a never-ending treadmill, your team going nowhere fast. Thus, the Hinkie strategy: tear down the structure and create a new foundation, mortgage present assets for potentially more valuable future assets, and create an opportunity to onboard transcendent players. And after several years working on an extreme makeover, the 76ers are now—without Hinkie—a legitimate championship contender with two transcendent pieces (Joel Embiid and Ben Simmons) flanked by talented veterans eager to play with the young stars. Hinkie made the phrase “Trust the Process” famous and gives us a better word than tanking: processing.

Accepted philosophy

Although no NFL owners or general managers have been completely open in their “processing” philosophies, leadership in other sports has been more transparent. Mark Cuban admitted one year that once his Mavericks were eliminated from the playoffs, coaches opted for younger players over veterans. And the Houston Astros, now a model Major League Baseball franchise with sustained success, were honest about their years of “processing” towards their now-sustained success. The process is being trusted throughout team sports.

In my sports law class, I teach about a case, Finley v. Kuhn, in which MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn successfully vetoed purported “tanking” (although that word was not part of the sports lexicon back in 1972) by Oakland A’s owner Charles Finley. Fresh off a couple of championships, the A’s attempted to sell off three star players to the Red Sox and Yankees (some things never change). And in 2011, NBA commissioner David Stern disallowed a trade of Chris Paul from the New Orleans Hornets (now Pelicans) to the Lakers, although Stern said he was acting as the Hornets owner rather than commissioner, as the team was being run by the NBA while in receivership.

Despite the examples above, leagues now consistently allow “processing” throughout team sports. It is understood that there are various accepted ways to build a roster; the idea of Roger Goodell—or anyone else—intervening in Dolphins management, even after it traded away Tunsil and Fitzpatrick, is one that we don’t even contemplate.

We accept, as the league office does, that NFL teams are built in different ways, some with older and expensive rosters trying to “win now” and some in various stages of processing. The problem is that some of those “win now” rosters don’t win and have delayed roster development to be back to where they started, which is … mediocrity.

Every successful veteran player was once an inexperienced young player, sometimes only given an opportunity due to an injury to someone ahead of him. Successful front offices (such as the one I worked in for nine years in Green Bay) almost universally prioritize developing young talent. It is not only part of but often the most integral part of an organizational philosophy to achieve sustained success.

The NFL waiver wires in February and March are full of veterans who have been released to make room for younger players; are these teams releasing older players—to be presumably replaced by younger ones—tanking? Of course not, it’s simply the very short cycle of life for NFL players. My point is that we often dismiss “processing” in favor of other organizational strategies, such as signing a bunch of free agents, but “processing” is more common than you may know.

Dolphins vs. other “non-tanking” teams

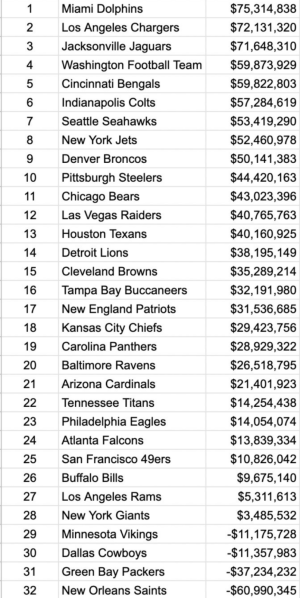

Next year the Dolphins will have more than $100 million in cap room to go along with three first-round picks, two second-round picks, one third-round pick and 14 picks in total. And in 2021 they now have two first=round picks and two second-round picks.

The Jets went on a spending spree this offseason, paying “retail” for free agents such as LeVeon Bell, C.J. Mosley, Kelechi Osemele, Jamison Crowder and others. The Bengals have been a study in mediocrity with no heir apparent to quarterback Andy Dalton, currently in the last year of his contract. Washington’s roster has two veteran quarterbacks, a rookie quarterback now playing and an incumbent injured quarterback accounting for more than $21 million on their cap. And their best player, Trent Williams, refuses to show up to work. All of these teams are currently winless. Certainly an argument can be made that the “processing” Dolphins are better off than any of these non-processing teams.

The Dolphins have traversed various strategic models of team building over the past decade, often with big swings with free-agent signings such as Mike Wallace and Ndamokung Suh. Now, with a new coach and general manager plucked from the same system (the Patriots), they appear committed to avoiding quick fixes. Rather, they are “processing” to — as the plan goes — put them in position for long term success. And, to observers of the Dolphins failed strategies over the past decade, why not?

As with everything, time will tell. Trust the, well, you know…

Let’s examine what exactly this “tanking” philosophy is and whether it makes organizational sense. I believe we definitely need a better word for this philosophy. And I know just the word:

“Processing”

Tanking implies that the entire organization embraces losing on purpose. Of course, that is not true. Players are still blocking, tackling, running; coaches are still working on game plans and schemes. So let’s be clear: This concept clearly does not apply to the active participants. Where the line becomes much less clear is with the management, although it is a philosophy long used in business and even sports.

Businesses regularly sacrifice short-term success for a more stable long-term future. Jeff Bezos has said that if Amazon has a good quarter (it has had a few), it is because of work and decision-making done three to five years ago. This certainly applies to sports. Successful teams in 2019 formed their roots in 2015-2018.

Unbeknownst to me, I was neighbors with former Philadelphia 76ers general manager Sam Hinkie for several years. When I saw him at a conference a few years ago—we had never met—he came right up to me and said: “You’re fast!” “Excuse me?” “We lived down the street from you; I used to see you run by our house all the time. You're fast!” I’ll take it.

I have talked to Hinkie about the philosophy he brought to the NBA. He had learned through research and analysis that playing on the fringes of the playoffs amounted to being on a never-ending treadmill, your team going nowhere fast. Thus, the Hinkie strategy: tear down the structure and create a new foundation, mortgage present assets for potentially more valuable future assets, and create an opportunity to onboard transcendent players. And after several years working on an extreme makeover, the 76ers are now—without Hinkie—a legitimate championship contender with two transcendent pieces (Joel Embiid and Ben Simmons) flanked by talented veterans eager to play with the young stars. Hinkie made the phrase “Trust the Process” famous and gives us a better word than tanking: processing.

Accepted philosophy

Although no NFL owners or general managers have been completely open in their “processing” philosophies, leadership in other sports has been more transparent. Mark Cuban admitted one year that once his Mavericks were eliminated from the playoffs, coaches opted for younger players over veterans. And the Houston Astros, now a model Major League Baseball franchise with sustained success, were honest about their years of “processing” towards their now-sustained success. The process is being trusted throughout team sports.

In my sports law class, I teach about a case, Finley v. Kuhn, in which MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn successfully vetoed purported “tanking” (although that word was not part of the sports lexicon back in 1972) by Oakland A’s owner Charles Finley. Fresh off a couple of championships, the A’s attempted to sell off three star players to the Red Sox and Yankees (some things never change). And in 2011, NBA commissioner David Stern disallowed a trade of Chris Paul from the New Orleans Hornets (now Pelicans) to the Lakers, although Stern said he was acting as the Hornets owner rather than commissioner, as the team was being run by the NBA while in receivership.

Despite the examples above, leagues now consistently allow “processing” throughout team sports. It is understood that there are various accepted ways to build a roster; the idea of Roger Goodell—or anyone else—intervening in Dolphins management, even after it traded away Tunsil and Fitzpatrick, is one that we don’t even contemplate.

We accept, as the league office does, that NFL teams are built in different ways, some with older and expensive rosters trying to “win now” and some in various stages of processing. The problem is that some of those “win now” rosters don’t win and have delayed roster development to be back to where they started, which is … mediocrity.

Every successful veteran player was once an inexperienced young player, sometimes only given an opportunity due to an injury to someone ahead of him. Successful front offices (such as the one I worked in for nine years in Green Bay) almost universally prioritize developing young talent. It is not only part of but often the most integral part of an organizational philosophy to achieve sustained success.

The NFL waiver wires in February and March are full of veterans who have been released to make room for younger players; are these teams releasing older players—to be presumably replaced by younger ones—tanking? Of course not, it’s simply the very short cycle of life for NFL players. My point is that we often dismiss “processing” in favor of other organizational strategies, such as signing a bunch of free agents, but “processing” is more common than you may know.

Dolphins vs. other “non-tanking” teams

Next year the Dolphins will have more than $100 million in cap room to go along with three first-round picks, two second-round picks, one third-round pick and 14 picks in total. And in 2021 they now have two first=round picks and two second-round picks.

The Jets went on a spending spree this offseason, paying “retail” for free agents such as LeVeon Bell, C.J. Mosley, Kelechi Osemele, Jamison Crowder and others. The Bengals have been a study in mediocrity with no heir apparent to quarterback Andy Dalton, currently in the last year of his contract. Washington’s roster has two veteran quarterbacks, a rookie quarterback now playing and an incumbent injured quarterback accounting for more than $21 million on their cap. And their best player, Trent Williams, refuses to show up to work. All of these teams are currently winless. Certainly an argument can be made that the “processing” Dolphins are better off than any of these non-processing teams.

The Dolphins have traversed various strategic models of team building over the past decade, often with big swings with free-agent signings such as Mike Wallace and Ndamokung Suh. Now, with a new coach and general manager plucked from the same system (the Patriots), they appear committed to avoiding quick fixes. Rather, they are “processing” to — as the plan goes — put them in position for long term success. And, to observers of the Dolphins failed strategies over the past decade, why not?

As with everything, time will tell. Trust the, well, you know…