The making of Emoni Bates’ next chapter

Maybe this is what they meant. The hype men. The prophesiers. Those preaching the next coming. Emoni Bates, in an NBA arena, crowd in his hands, sneer in his smirk. He peels off around a thicket of screeners, snagging a baseline inbound in the near corner. Pause. Swivel. Two dribbles right. Between the legs, back left. Two dribbles to the baseline. Stop, step back off his left foot. Ball in the air. The soundtrack: “Ohhhh!” No follow-through. Bates bobs his head, hopping and bounding back down the floor.

Now the place is turned up. It’s early November, the new season underway, and this — a grand reveal. Fifteen thousand in the house, wondering what Bates will do next. A rebound caroms off the back iron. Here he comes!

This cheer louder than the last. A put-back dunk ready for the highlight reels. Sure, Bates pops off, says some choice words, draws a technical foul. But who cares? An awesome scene.

Back in the day, this is what was foretold.

That is, except for everything that wasn’t.

In an alternate universe, maybe Emoni Bates would simply be a highly touted freshman starting his journey in college basketball. A 6-foot-10 beanpole of potential, nothing more. Maybe he’d have never hit fast-forward, never skipped a year of high school. Maybe, further back, he’d have never been a YouTube star or a Sports Illustrated cover boy. Maybe he’d never been an unwitting protagonist in the morality play of how young phenoms are pumped and puffed, profited off of, judged through a lens they never asked for, then pilloried, picked apart, and left to figure it out for themselves.

But he was.

And now he’s here.

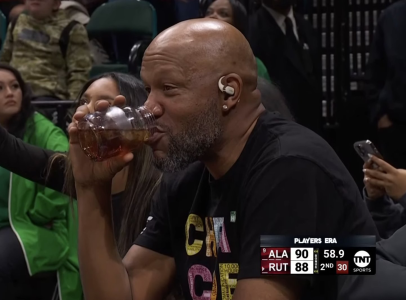

It’s late October, and Stan Heath is sitting perched a few rows up from the floor at Eastern Michigan University. He’s wondering how this is all going to work. The 57-year-old is beginning his second season as head coach of his alma mater. He’s grown out a cropped gray beard for 2022-23. “This kid … ” he says, shaking his head, pausing, wanting that word to set in, offering a reminder that’s often either forgotten or ignored when it comes to the journey of Emoni Bates.

“Is still only 18, man.”

He is. Yet, Bates’ story is often spoken of as reaching a point of critical mass. If not now, when? If not here, where? This constant, intense urgency, always. It’s resulted in a life lived in overdrive:

Declared a prodigy in seventh grade, cover of SI at 15, committed to Michigan State at 16, star pupil of a makeshift school conjured from his father’s imagination the next year, a decommitment from Michigan State, an ill-fated season with Penny Hardaway and the Memphis Tigers at 17, a draft ranking in decline, then a dip into the transfer portal, a lack of options, a commitment to the unlikeliest landing spot and, this fall, a screeching skid — the kind of headlines that trace a falling star.

Turns out there’s one problem with being a surefire NBA star at age 14. Time is just as likely to work against you as it is with you.

“Eighteen, man,” Heath stresses.

EMU’s afternoon practice is wrapped up. Players milling around. A local high school team sat in for the last two hours, quietly observing. They watched the Eagles play, but all eyes followed Emoni. Every step.

Not long ago, crowned a young king, Bates filled this building to the top. An outsized star in an undersized town, he represented something bigger than basketball in Ypsilanti. The city is wedged between Ann Arbor and Detroit. An optimist might say it’s overlooked, a pessimist might say it’s forgotten. Around here, it was thought Bates might go off into the world and be to this part of southeast Michigan what LeBron was, and is, to northeast Ohio.

But now? Reality is a matter of necessity. Bates is back in Ypsilanti, back where it all began. In the movie version, this would be a waxy tale of a kid wanting to bring his hometown school into the spotlight. But this ain’t that. In truth, he’s come home to salvage his pro prospects and rewrite his story, one that many out there already decided is over.

“Everything he’s been given,” Heath says, “feels like a blessing and a curse.”

On the other side of the gym, those kids, the ones now standing next to Bates, posing for pictures, they don’t hear any of this. To them, Emoni is Emoni, and that means something.

Heath looks around the 8,800-seat arena, a building constructed when Eastern Michigan thought its men’s basketball program was going to be far bigger than it ever actually became. Today, second-level seats are covered in tarps. The lights are dimmed in those upper regions.

A visitor sitting next to Heath says, “You know, Stan, if this works — big if — but if it works, it could be big.”

“It could be,” Heath says. “There’s a special opportunity here.”

Speak to those around Bates’ re-recruitment last spring and you’ll find there was always way more smoke than substance. Michigan was seen as a major possibility. It was not. Louisville, Seton Hall and Arkansas were mentioned. Interest? Sure. Beyond that? Wasn’t happening. Some even said maybe Michigan State was back in play. No.

Ideally, to Bates and those surrounding him, he’d have entered the 2022 NBA Draft. Actually, most ideally, he’d have walked across that stage and shaken Adam Silver’s hand in 2021 or even 2020. But, born Jan. 18, 2004, and beholden to NBA rules, Bates has spent his recent past waiting to become eligible for the NBA Draft in 2023. There was hope in the last few years that the rule might change, but that never came. Instead, his professional career — and the gobs of money waiting with it — remained on some imaginary horizon.

So Bates had to play somewhere in 2022-23, and it wasn’t going to be Memphis. You might’ve heard that was messy. Everyone did. That’s why, from the moment Bates entered the transfer portal last April, speculation surrounding his future playing destination was smeared with stigma.

Those 2021-22 Memphis Tiger will go down as an all-time drama. Or maybe a tragicomedy, depending on how you looked at it. Bates and fellow freshman lottery pick prospect Jalen Duren joined a roster filled with returnees and upperclassmen in their early-to-mid-20s. Shockingly, it didn’t work out.

That preseason, Hardaway admitted the incoming freshman talent might result in some older players having “their feelings hurt.” He somehow wildly undersold this idea. By mid-December, a preseason top-10 team was 5-4. Openly frustrated, Hardaway vented: “I didn’t think it would be like this. This is a tug of war over who wants to be the man.”

Bates began missing games, citing back issues. Amid speculation he might be leaving the program, he reappeared on campus with Nike gift packages for his teammates. At the same time, it was a poorly kept secret that some deep frustrations existed and the family was exploring its options.

Bates returned for six games in January. The Tigers went 3-3, standing 11-8 overall, going nowhere. Then he exited the lineup again, and Memphis won 10 of its last 12 games to snag an NCAA Tournament bid.

The year ended dolefully. Bates appeared for three minutes in a first-round NCAA Tournament win over Boise State, then played 12 minutes, going 1-of-5 from 3-point range, in a four-point loss to Gonzaga. By then, it was a foregone conclusion that he’d be playing elsewhere in 2022-23, whether collegiately or some professional option. The G League? Maybe Europe?

Problem was, Bates’ baggage was heavier than ever. Voices wondered aloud if he was a good teammate. Stories bounced around back channels of Bates’ parents regularly attending practice at Memphis. One 2021-22 staff member, speaking on the condition of anonymity, estimates that was the case “probably three out of every four practices,” adding: “Very hands-on. Very involved.” This was common knowledge. The typical refrain among those considering pursuing him: Is the talent worth everything else that comes with it?

“It’s a hard line to walk,” said the staff member.

Fact is, though, had Bates shown out at Memphis, none of that would’ve mattered. Everyone would want him. But, most worrisome, that season in Memphis exposed some warts. He was erratic, inefficient. The numbers spelled it out — the Tigers were better with him off the floor than on, and won more, too. Whoever went after Bates, would have to solve that math.

Enter Stan Heath.

A 1987 EMU grad, Heath returned to Ypsilanti in April 2021 to take over a floundering program with four NCAA Tournament banners hanging about those upper deck seat draped in tarps. Most known for college head coaching stints at Kent State, Arkansas and South Florida, he spent 2017–2021 as head coach of Orlando’s NBA G League affiliate, the Lakeland Magic.

Heath hadn’t followed much of Bates’ rise to stardom, he says, “but I knew the name.” Arriving at EMU, he tried to recruit some players from Ypsi Prep, the ephemeral high school/basketball team created by his father, EJ Bates, to courier Emoni through his junior year in 2020-21. Heath landed a guard, Orlando Lovejoy, who happens to be one of Emoni’s closest friends, but he never actually recruited Bates.

“Didn’t think in a million years he’d be at Eastern Michigan,” Heath says.

One year later, things changed. Needing an independent opinion on Bates, Heath reached out to Larry Brown. At 82 years old, the hall of famer carries the rep as 1) one of the unique minds in basketball, and 2) a conduit to troubled stars. He spent last year in Memphis as an assistant amid all that gossip and hyperbolic attention.

Brown first saw Bates in the summer of 2021 at Peach Jam. Bates launched his first 3-pointer from about 40 feet, and Brown turned and walked away. He eventually returned, though, watching Bates more and more, seeing all the innate gifts.

“And I kinda fell in love with him,” Brown says.

It was, Brown says, just a matter of seeing what’s underneath all the surrounding commotion. Seeing what could be.

Brown gave Heath his version of what happened at Memphis. Bates was 17, facing massive expectations, playing with and against grown men. He didn’t arrive until late August, missing hugely important summer months of college integration. He was, perhaps most confoundingly, a 6-foot-10 wing pursuing the idea of playing point guard.

“He was out of position,” Brown says now. “We might not have been fair to him. You know, if we could do it all over again … “

Brown told Heath (and other coaches who called) about the version of Emoni Bates that doesn’t get the attention. The player who knocked on his door daily to watch extra film. The one who is “receptive to coaching” and “lived in the gym.” And when it comes to EJ Bates ….

“I told (Heath) that I know the perception, but I’m not into perceptions,” Brown says. “The dad is involved, but he really means well. The kid loves his parents. They just want to protect him.”

On the other end of the phone, Heath nodded along.

“Larry is a straight shooter,” Heath says. “He told me exactly what I needed to know. He said, ‘Stan, listen, don’t believe what everyone says. I’m telling you, that kid is coachable.’ I was sold.”

So now, like that, Stan Heath is Emoni Bates’ coach. He sees a young man who has spent his teenage years in a glass box. He sees a player who, if he uses his gifts and plays between the lines, 94 x 50, can be an elite talent

He also sees a vulnerable 18-year-old and wants to help.

“One of the things I’ve learned about (Bates), and I understand it, is that it’s hard for him to trust people,” Heath says. “Outside of a few people, it’s hard for him, and I understand why, because you don’t know what everybody wants from you, what their agenda is, what they want to gain from him. That’s the struggle in the world he lives in.”

Is there a risk in Heath bringing in Bates? Maybe.

But there’s also incredible possibility. Though judged by a public spotlight he’s stood in since about 2017, Bates will be the youngest player on the floor in most games EMU plays this year. There’s still so much time to get this story right.

Bates wasn’t made available to speak for this piece. He exists, as he nearly always has, in a bubble. EJ Bates, meanwhile, declined to speak via a third party.

There is, though, this parting thought from a 2021 interview.

“It’s so near, yet it’s so far away,” EJ Bates said of the future. “I tell people that all the time. And things can happen between now and the next 20 minutes.”

It’s the evening of Sept. 18 at the intersection of Nottingham Drive and Clark Road in Superior Township, Washtenaw County — a few miles from the Eastern Michigan University campus. Red and blue lights.

Two officers approach the car. The video, one later obtained by multiple outlets, shows Bates turn and look up and out from the driver-side window. Fear in his eyes, heat in his chest.

The deputy at the driver-side window says the vehicle rolled a stop sign. Then, recognizing the face staring back at him, the officer, sounding a bit flummoxed, says, “You Emoni?”

“Yeah.”

Bates hands over ID and says the vehicle is borrowed. His car, he says, is in the shop.

Back in the police cruiser, one officer says to the other, “That’s Emoni Bates. NBA player.”

“Oh,” the other says. “No kidding.”

After running Bates’ name and plates, the officers return to the car.

“Here’s the issue,” the deputy says. “I smell weed coming from this car right now.”

Bates admits to having just smoked marijuana at his cousin’s house and says there’s a bag in the car. The deputy tells Bates to step out of the car, and suddenly things become very real. Bates raises his hands. Pressing his eyes closed, he tells the deputy there’s also a gun in the vehicle.

“I ain’t gonna lie, sir, you might as well just cuff me up right now,” Bates says.

Handcuffed and crammed into the back of the police cruiser, Bates breaks down into tears. He’s permitted to use his cell phone and calls his parents.

“I messed up,” he says, hunched over, speaking into a phone held behind his back.

The footage is hard to watch. Raw and clear. Steve Haney, a longtime prominent attorney and former NBA agent, represented Bates against charges of carrying a concealed weapon and altering ID marks on a firearm. Potential penalties of multiple years in prison and thousands of dollars in fines were on the table.

The arrest was on a Sunday night. News broke the following morning.

Plenty of voices were quick to analyze, theorize, criticize. Haney, fielding calls from multiple reporters, told everyone to reserve judgment until the facts came out. He said Bates never had any previous legal issues. He said there was more to the story and, in time, made that case to the court.

“We felt after reviewing the evidence that there were some issues with the stop,” Haney explained recently. “We raised those issues with the prosecutors. There were some other evidentiary problems that we identified. Fortunately, we had a reasonable prosecutor who wanted to do what was right for a kid who was 18 and made a mistake. At the end of the day, he borrowed a car with a gun with it.”

Bates was placed in a youthful diversion program. Once completed, no criminal conviction will exist and the case will be dismissed. The program consists of non-reporting probation and seeking mentorship counseling, and is contingent on Bates staying out of trouble. If he violates the program, a misdemeanor conviction will be re-entered.

EMU originally suspended Bates from all class and athletic activities. That punishment was lifted on Oct. 14 when the felony charges were dropped.

“Look, I think, without question, he understands the gravity of it and appreciates the second opportunity that he’s going to get here,” Haney continued. “A lot of kids in this situation, not that he got special treatment, but a lot of kids don’t get a second opportunity.”

So this is now part of Bates’ story. Another chapter in a complicated book. In truth, it all could’ve gone so much worse.

But it didn’t.

And Emoni Bates still has the chance that’s ahead of him.

Eastern Michigan averaged 1,629 fans per game last year. Friends, family and a few diehards of a program that hasn’t won the Mid-American Conference since 1998.

For its opening exhibition game of 2022-23, though? A crowd of 2,487, buzzing.

Emoni answered with 27 points. Fans howled for every dunk, every 3. More importantly, after being chided by Heath for not rebounding in practice, Bates grabbed six boards. He brought the box score to his coach after the game and pointed to the column.

“See, that’s the guy I know,” Heath says. “I don’t know the guy everyone else is talking about.”

EMU’s first official home game of the season was Nov. 7 against Division II Wayne State. You ready? …. 4,677 people showed up. The fourth-largest crowd in the arena’s 24-year history.

They didn’t know beforehand that the star of the show wasn’t going to dress or play. Bates was held out of the opener in what was described by the program as a coach’s decision. Per a person close to the program, speaking on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly, the absence wasn’t related to any new incident or issue.

So now it’s Nov. 11. A Friday night in Detroit. EMU is facing Michigan in what’s expected to be a home game for the big school in Ann Arbor. This is, for all intents and purposes, a menial game on a menial date. Two things feel particularly inconsequential in November — college basketball and Christmas music.

This night, though? It takes on a life of its own. The Emoni Bates Experience, in all its glory. Shots falling, crowd calling. He’s wearing Nikes because he can. EMU is contracted with Adidas, but whatever, apparently. Emoni has long been a Nike Man. The company sponsored both his grassroots program and Ypsi Prep. So he’s wearing Nikes and the EMU athletic department is only offering a “no comment” on the topic.

The building is pulsing.

Then, Bates, already sitting on 14 first-half points, does this.

EMU athletic director Scott Wetherbee, soon after, is nudged by his university’s director of facilities who oversees what’s now called the Gervin Center back in Ypsilanti.

“The tarps are coming off,” he says.

Bates will finish with an electric 30 points in a narrow loss. All it takes is one night and, just like that, a familiar conversation begins anew.

“Looking at NBA games today, you see a lot of that,” says Michigan coach Juwan Howard. “You see some guys that get paid a lot of money that make shots like Emoni, can score similar to Emoni and have that size.”

Everyone is talking about the highlights, but more tellingly, in the waning moments of the game, Bates is up on his feet during a timeout, speaking his mind, pumping his fist. The EMU huddle, all eyes on him, nods along. Then they all stand, arms up, perched together.

As it turns out, after the arrest, Bates met privately with his teammates. He stood in front of them and apologized. He told them that, more than anything, he wants to be part of a team.

“He wants to be one of the guys,” Heath explains, “because he’s never really had that.”

Redemption is hard, but comes easier to the young. For Emoni Bates, everything that’s happened can, in time, be consigned to a past. It doesn’t matter what was foretold when he was a kid. Maybe everything from now on can be what he makes of it. Maybe he can just play.