We’re supposed to be living in the future by now. To an entire generation of Americans,1 “2015” has long been shorthand for a quasi-utopic vision of better living through technology. In its depiction of 2015, Back to the Future Part II promised us flying cars, hoverboards, and pizzas that get rehydrated to perfection in two seconds. It also promised us video phones, enormous flat-screen TVs, and virtual-reality headsets, but it’s human nature to focus on the things we don’t have over the things we got used to five years ago. (And self-lacing shoes are on their way.)

But now that 2015 is upon us, there’s only one scene from Back to the Future Part II that really matters, and it’s this one:

“Yeah, it’s something, huh? Who would have thought? 100-to-1 shot! I wish I could go back to the beginning of the season, put some money on the Cubs.”

As far as predictions from the movie go, you’re better off counting on us getting flying cars — maybe Elon Musk will release the mother of all software updates for the Tesla before October — because this prophecy isn’t coming true. No, not the part about the Cubs winning the World Series — the other part. As Opening Day approaches, you can’t get 100-to-1 odds on the Cubs anywhere. Far from being the longest of shots, the team that has lost more games over the last five years than any except the Astros is now everyone’s preseason darling.

Relics are once-ordinary objects that, by dint of suffering and the long passage of time, acquire a sacred patina. By that definition, the Cubs front office is seeking the holiest relic in the history of American sports: a Chicago Cubs world championship, the last of which, claimed in 1908, has almost certainly receded beyond the memory of any living Cubs fan.2

As with most relics, attaining this one will require not just talent and perseverance, but some kind of divine providence, because baseball’s current playoff structure introduces an uncontrollable element of randomness into the quest. The Cubs front office has no solution to that problem. No one does.3 But though Cubs president Theo Epstein and GM Jed Hoyer can’t guarantee a world championship, they can guarantee the next best thing, which has been nearly as elusive on the North Side: a consistent contender.

The Cubs have been consistently good at times (they managed six straight winning seasons from 1967 to 1972) and sporadically great at others (the 1984 team won 96 games and is still remembered as fondly as any non-pennant-winning club in modern history). But they haven’t been both in ages.

Consider this: The Cubs have not won 90 games in consecutive seasons since 1930. That streak goes a long way toward explaining The Streak, and is nearly as improbable. That’s also the streak that the front office has the power to end. The postseason is a lottery, but you can’t win if you don’t play, and Epstein and Hoyer have the Cubs poised to hold a lot of tickets. It is their acumen, in fact, that has ruined the movie’s prophecy.

We weren’t supposed to be living in this future just yet. The Cubs have been building toward better days since the moment Epstein and Hoyer were hired after the 2011 season, but the pair inherited such an old, expensive, and bad roster (and a weak farm system to boot) that it seemed foolishly optimistic to think the club would be ready to contend by 2015. As recently as last March, when I looked in on the state of the franchise, I hedged my bets on the time frame despite being exceedingly optimistic about the team’s long-term future. The most I was willing to commit to was that “The Cubs may not get past the Cardinals, but a spot in the 2015 wild-card game is worth reaching for.” As recently as last October, even Cubs fans were still unwilling to buy in, judging from the 50-to-1 odds you could have gotten on a 2015 world championship at the time.

And then, somewhere between the October hiring of manager Joe Maddon and the December signing of ace Jon Lester, a dam broke, and baseball fans nationwide suddenly realized that this sleeping giant of a franchise had awoken from its extended hibernation. This winter’s liberal dispensation of cash eroded the hard-earned cynicism of Cubs fans who were skeptical of ownership’s promise to spend money as soon as the front office asked for it. After years of entrenched pessimism, the collective mood has turned so exuberant that Alan Greenspan would denounce it. The Vegas odds on the Cubs winning the World Series dropped as low as 6-to-1 a few weeks ago, presumably because Cubs fans were delirious from priapism after seeing this in spring training:

While it may have taken the Cubs hiring one of the game’s best managers and signing one of the game’s best free agents for everyone to notice, the fact is that the groundwork for one of the quickest-loading bandwagons in recent sports history was laid before this offseason began. The 2014 Cubs may have been terrible, but 2014 wasn’t terrible for the Cubs.

It was actually pretty spectacular. Here’s just a partial list of the good things that were happening while the Cubs played possum with a 73-89 record:

• First baseman Anthony Rizzo, who slumped to a .233/.323/.419 line in 2013, hit .286/.386/.527 with 32 homers and finished 10th in NL MVP voting. Rizzo is under team control through 2021.

• Shortstop Starlin Castro, who also slumped in 2013 by hitting .245/.284/.347, also bounced back in a big way, hitting .292/.339/.438. Like Rizzo, Castro set a career high in OPS+, and like Rizzo, Castro enters this season at just 25 years old. Castro is under team control through 2020.

• Third baseman Kris Bryant, the no. 2 overall pick in the 2013 draft, had set extreme expectations for himself after hitting .336/.390/.688 in a 36-game 2013 pro debut. He then obliterated those expectations in 2014, hitting .325/.438/.661 between Double-A and Triple-A and leading the minors with 43 homers. Baseball America ranks him as the no. 1 prospect in baseball.

• Right fielder Jorge Soler, who had signed a nine-year, $30 million contract with the Cubs after he defected from Cuba in 2012, had a difficult 2013. He hit .281/.343/.467 in A-ball, good but not overwhelming numbers, and appeared in only 55 games before a stress fracture in his left tibia knocked him out of action. He also got suspended for five games for charging the opponents’ dugout with a bat.

Soler started 2014 by missing two months with hamstring issues, but once he was healthy he needed only 22 games in Double-A, where he hit .415 and slugged .862, to earn a promotion to Triple-A, where he hit .282/.378/.618 in 32 games. Promoted to the majors in late August, Soler became the third player in the last 100 years4 to mash an extra-base hit in each of the first five games of his career. He hit .292/.330/.573 in his 24-game audition with the Cubs. Baseball America rates Soler as the no. 12 prospect in baseball.

• Jason Hammel, who had signed a one-year contract with the Cubs after posting a disappointing 4.97 ERA in Baltimore in 2013, had the best season of his career, managing a 2.98 ERA in his 17 starts before being traded to Oakland. Hammel rejoined the Cubs this offseason on a very reasonable two-year, $20 million contract.

• After two promising seasons in the rotation in 2012 and 2013, Jeff Samardzija broke out in 2014, posting a 2.83 ERA in his first 17 starts before also being traded to Oakland.

• In exchange for a half-season of Hammel and a season and a half of Samardzija,5 A’s GM Billy Beane decided to go for broke, surrendering Addison Russell, Billy McKinney, and Dan Straily.

Russell, who was just 20 years old last season, hit .295/.350/.508 in Double-A and is considered an elite defensive shortstop; he frequently gets compared to Barry Larkin, and Baseball America rates him as the no. 3 prospect in baseball. McKinney, an outfielder whom the A’s drafted in the first round in 2013, was hitting .241/.330/.400 at the time of the trade, but hit .301/.390/.432 after, as a 19-year-old in high-A ball. He also made Baseball America’s Top 100. Straily is now with Houston due to another trade I’ll get to in a bit.

• Javier Baez, who hit 37 homers between A-ball and Double-A in 2013, continued to show freakish power for a middle infielder, hitting 23 homers in 104 games and slugging .510 in Triple-A in 2014 before being promoted to the majors. In Chicago, Baez showed potentially huge power with nine homers in 52 games, but that display was often overshadowed by his massive contact issues, as he hit .169 and struck out in 41 percent of his plate appearances. He has as much variance as any young player in the game today, but his upside is enormous.

• Arismendy Alcantara elevated himself as a prospect by hitting .307/.353/.537 in his first taste of Triple-A, earning a call-up in July. While he hit only .205/.254/.367 in Chicago, he showed good defensive chops at both second base and in center field. Given his ability to play multiple positions and switch-hit, Alcantara figures to be a key element of this year’s team as a super-utility man.

• Left fielder Chris Coghlan, signed as a free agent after several lost seasons in Miami, found his way into the lineup and hit .283/.352/.452 in 125 games, his best performance since his Rookie of the Year season in 2009.

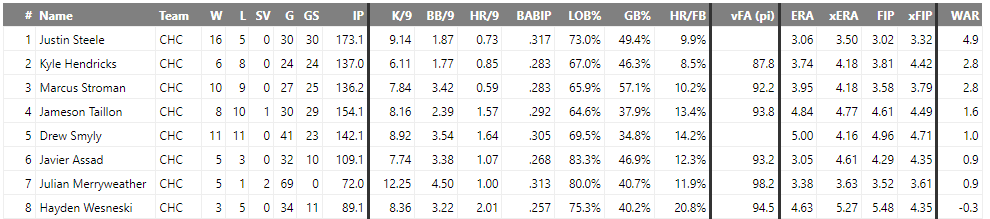

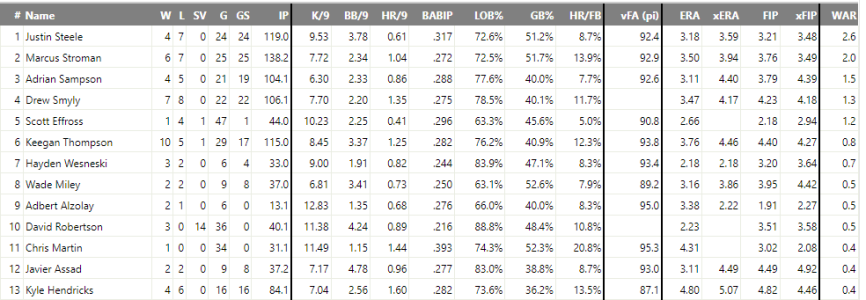

• Right-handed starter Kyle Hendricks, one of two prospects the Cubs acquired from Texas for Ryan Dempster at the trade deadline in 2012, was called up in July and was sensational, posting a 2.46 ERA in 13 starts despite a fastball that averaged 88 mph and just 47 strikeouts in 80.1 innings. Between his lack of velocity and strikeouts, there’s no way he can continue to be that effective, but Hendricks’s elite command of all of his pitches keeps him from making mistakes both outside the strike zone (walks) and inside (homers). Plus, his ERA could jump a point and a half and he’d still be an effective no. 4 starter.

• Jake Arrieta became the biggest breakout pitcher in baseball. Despite excellent stuff, Arrieta had been a huge disappointment in Baltimore, posting a 5.46 ERA over parts of four seasons. The Cubs were intrigued by both his stuff and his peripheral numbers — his FIP in Baltimore was nearly a full run lower than his ERA — and acquired him in 2013 in exchange for three lost months of Scott Feldman.

In his first full season with the Cubs, Arrieta made some mechanical tweaks, perfected a slider that he can manipulate as if it’s three different pitches, and kicked the ever-loving crap out of the National League. His 2.53 ERA in 25 starts actually underrates him; with 167 strikeouts, 41 walks, and just five homers allowed in 156.2 innings, his 2.26 FIP was the second-best in the majors among pitchers with 100 or more innings, behind only Clayton Kershaw. It was just one season, and there’s always the possibility that it was a stone-cold fluke. But in 2014, Arrieta was a bona fide no. 1 starter. And it’s worth noting that Samardzija, the last Cubs pitcher to improve so dramatically from one year to the next, kept getting better and better after breaking out. There’s a reason pitching coach Chris Bosio has such a strong reputation.

• The Cubs had the no. 4 pick in the June draft and selected catcher/outfielder Kyle Schwarber out of Indiana University. The jury is still very much out on whether Schwarber can develop the defensive chops to stick behind the plate, but after mashing .344/.428/.634 in his pro debut and advancing to high-A ball barely a month after signing, his bat looks like it will play at any position. He’s just the fourth-best hitting prospect in the organization, but Baseball America ranks him as the no. 19 prospect in the game.

• Maddon unexpectedly opted out of his contract with the Tampa Bay Rays shortly after their GM, Andrew Friedman, joined the Dodgers. With arguably the game’s best manager suddenly available, the Cubs made the cold, ruthless, and correct decision to part with incumbent Rick Renteria — who had committed no fireable offenses in his one year at the helm — and hire Maddon.

• The Cubs landed Lester, the second-best player on the free-agent market (behind Max Scherzer) and their top target. And because Lester had been traded to Oakland at the deadline, he did not have draft pick compensation attached to him. The Cubs would have signed him anyway; getting to keep their second-round pick in this year’s draft was just a bonus.

• The bullpen, which was a mess in 2013 (ranking 13th in the NL with a 4.04 bullpen ERA), was much improved. Pedro Strop, also acquired in the Feldman trade after allowing 19 runs in 22.1 innings for the Orioles in 2013, returned to his 2012 form immediately after the trade; he threw 61 innings for the Cubs last year with a 2.21 ERA. Justin Grimm and Neil Ramirez, who were starters in the Rangers’ system when the Cubs acquired them in the Matt Garza trade, both shone after a move to the bullpen. And Hector Rondon, who had an uneven rookie season as a Rule 5 player in 2013, was a revelation in 2014: He somehow cut his walk rate in half while increasing the average velocity on his fastball from 93.0 to 95.0 mph. Strop, Ramirez, and Rondon made the Cubs one of just six major league teams that had three relievers (minimum: 50 games) with an ERA under 2.50 last season.

Counting Baez as a second baseman and Alcantara as a center fielder, the Cubs had a player take a significant step forward at every position except catcher. They saw two starting pitchers and half the bullpen make a similar leap. And they added the no. 3, no. 19, and no. 83 prospects in the game.

Even before Lester and Maddon started hogging the headlines, 2014 was a damn good year, the kind that could pay dividends for the franchise well into erstwhile Cubs fan Hillary Clinton’s6 second presidential term. Coghlan will be 30 in June and a free agent in two years, but every other position player listed above is under club control through at least the 2020 season.

Despite all of that good news, though, the Cubs lost 89 games. This was partly by design, of course. Bryant and Russell didn’t get any time in the majors, and Soler played just 24 games. Meanwhile, guys like Junior Lake (.211/.246/.351), Mike Olt (.160/.248/.356), and Nate Schierholtz (.192/.240/.300) got nearly 1,000 plate appearances in extended auditions from a team without any ambitions of playing meaningful baseball in 2014.

While they couldn’t salvage anything from Lake, Olt, or Schierholtz, the Cubs got enough from utilityman Emilio Bonifacio and left-handed specialist James Russell to trade them both to Atlanta for a legitimate catching prospect in Victor Caratini. And their decision to give former utilityman Luis Valbuena an everyday job paid off when Valbuena had the best season of his career, hitting .249/.341/.435 with 16 homers and 33 doubles. After the season, the Cubs were able to package Valbuena (whose job Bryant was about to take) and Straily to Houston for Dexter Fowler, who filled the Cubs’ dual need for a center fielder and leadoff hitter.

On the mound, all of the good work done by Arrieta, Hendricks, Hammel, and Samardzija was undone by the fact that the two guys who made the most starts for the 2014 Cubs were Travis Wood, who posted a 5.03 ERA in 31 starts, and Edwin Jackson, who was allowed to throw 141 innings despite a 6.33 ERA. Jackson was worth negative 2.3 Wins Above Replacement per Baseball-Reference.com, making him the worst player in the major leagues. Of the six starters who threw the most innings for the Cubs last year, four had ERAs under 3.00, but thanks to the Samardzija-Hammel trade, they combined for just 72 starts. Meanwhile, the other two were so bad that the team’s overall rotation ERA was 4.11, 13th in the NL.

This year, three of the four good starters return, with Lester taking Samardzija’s spot. The Cubs have no plans to be sellers at the deadline this year, so health permitting, Lester, Arrieta, Hammel, and Hendricks should make 120 starts in 2015. Jackson and Wood are fighting over a single rotation spot — or possibly sharing it, with Wood starting against lefty-heavy lineups and Jackson the reverse; Maddon is being coy about his plans — and if they don’t perform, they’ll be in danger of losing their spot once Tsuyoshi Wada or Jacob Turner heals up from injuries. Even with regression from Arrieta and Hendricks, the Cubs’ rotation as a whole should be significantly improved in 2015.

The Cubs have also further upgraded their pitching staff by giving their arms elite receivers to throw to. The ability to coax favorable calls on borderline pitches from the home plate umpire has finally come under the sabermetric spotlight in recent years, and the difference between a bad pitch framer and an elite one adds up, pitch by pitch, game by game, to dozens of runs each year. Incumbent catcher Welington Castillo had been one of the worst pitch framers in baseball.

While the Cubs were outbid at the last moment for Russell Martin, perhaps the best pitch framer in the game,7 they turned to a nice consolation prize in Miguel Montero. The former Diamondback will platoon with David Ross, who was also acquired in large part for his glovework, while Castillo is out in the cold, a third wheel on the roster waiting to be traded to a team desperate for catching depth. Various analyses of their pitch-framing abilities estimate that Montero was anywhere between 23 and 48 runs better than Castillo last season, while the difference between Ross and former backup John Baker was worth about eight to 10 runs. That means the Cubs have gained something like three to five wins for a skill that until recently was completely hidden from view.

Montero has made another kind of impact already: After having patiently built up the franchise’s most important asset, its farm system, adding the new backstop was an example of the Cubs bringing their other prime strength, their immense payroll space, to bear. The Cubs had an Opening Day payroll of more than $144 million in 2010, a number that dropped four years in a row as dead weights like Alfonso Soriano and Carlos Zambrano were shipped away or saw their contracts mercifully end. The 2010 Cubs had eight players on the roster making more than $12 million, but entering this past offseason, just one Cub (Jackson — oops) was under contract in 2015 for even $7 million.

This made it possible for the club to ink Lester to a six-year, $155 million contract; re-sign Hammel; take on Fowler’s $9.5 million 2015 salary;8 and acquire Montero, who had three years and $40 million left on his contract, while giving Arizona little more than salary relief in return.9 The Cubs’ ability to absorb contracts means that they can acquire talented but overpaid players while simultaneously holding on to their core of young talent, flexibility many franchises would envy.

Even with all of their offseason additions, and even as revenues soar throughout baseball, the Cubs’ Opening Day payroll will be around $117 million — $25 million less than it was five years ago. That’s why they were able to throw $5 million a year at Maddon, and why they made a halfhearted play for James Shields when Shields struggled to find a home in free agency. They weren’t more gung-ho on Shields because they’d rather make a play this coming winter for an even better starting pitcher to pair with Lester: David Price, Johnny Cueto, Jordan Zimmermann, Mat Latos, and Samardzija are all entering the final year of their contracts, and Zack Greinke has an opt-out in his.

The Cubs’ wealth of pre-arbitration players means that their 2016 payroll only figures to go up a few million dollars with their current roster, and after 2016, Edwin Jackson’s $13 million a year comes off the books. With no big-name free agents of their own to worry about — Fowler will be their only notable free agent this winter — the Cubs will have the revenue to add a Lester-class superstar each of the next two winters without breaking a sweat.

[COLOR=#red]The bottom line: Whatever happens in 2015, the Cubs are positioned to keep improving, meaning this will likely be the worst Cubs team of the next six years[/COLOR].

The worst Cubs team of the next six years looks like at least a fringe contender. Objective projection systems agree that the Cubs will be in the hunt for at least a wild-card spot: Baseball Prospectus has the Cubs at 84-78, with a 43 percent chance of making the playoffs, while FanGraphs projects them to go 83-79 with a 42 percent shot.

And yet, from where I sit, even those numbers seem low. The Cubs are absolutely poised to contend for not only a wild-card spot but the NL Central crown. Some of that optimism stems from considering their competition. Despite winning 90 games last year, the Cardinals outscored their opponents by only 16 runs all season. The tragic death of Oscar Taveras10 deprives them of their best prospect, and while new right fielder Jason Heyward gives them everything Taveras would have, he came at the cost of no. 3 starter Shelby Miller. The Pirates, meanwhile, lost Martin, who was worth 5.5 bWAR last year, and that stat doesn’t even account for his pitch-framing skills. Both teams are likely to be good; neither team is likely to be great. The Reds and Brewers aren’t even likely to be good.

But the main source of my optimism is that this isn’t an ordinary youth movement. For one thing, Bryant isn’t an ordinary prospect. He isn’t even an ordinary no. 1 overall prospect. His minor league performance is almost unprecedented; in particular, his .666 slugging average as a pro is higher than any minor league prospect’s in the last 30 years.11 In 174 professional games, Bryant has hit 52 home runs. And not that it means anything, but he leads the world in home runs this spring, with nine.

A good blueprint for Bryant’s rookie season is fellow third baseman Evan Longoria, who was the no. 3 pick in the draft in 2006, hit .299/.402/.520 between Double-A and Triple-A in 2007, and hit .272/.343/.531 in 2008 for the Rays, making the All-Star team and winning Rookie of the Year honors. Bryant could very well earn some MVP votes as a rookie, like Longoria did. (Bryant is so good that his downside is probably Alex Gordon, who was also a college third baseman drafted no. 2 overall, and who’s the only player other than Bryant to win Baseball America’s College Player of the Year and Minor League Player of the Year in consecutive seasons. When Gordon is your downside, you’re doing something right.)

And as with Longoria, who started his rookie season in the minors but was called up on April 12, the controversy over Bryant’s service-time status has more implications for the CBA than for his team. Whether or not the Cubs are within their rights to have Bryant start the year in the minors in order to gain an extra year of club control, the debate is a tempest in a teapot in terms of how it affects their ability to win this season.

Bryant may not be in the lineup when the Cubs host the Cardinals on Opening Night on April 5, but, barring injury, he’ll be up almost immediately after the requisite 12 days have passed.12 He’s probably going to play 140 games for the Cubs, and he’s probably going to win Rookie of the Year. And if he doesn’t, Soler might; Baseball America projects Bryant and Soler as the game’s top two rookies this year.13

While Bryant and Soler are as safe a bet as rookies go, none of the other young players the Cubs plan to open the season with is quite that can’t-miss. However, the Cubs have so much prospect depth that if their first wave doesn’t succeed, they can simply throw more out there until one sticks. Baez is still having swing-and-miss issues in spring training, and may return to Iowa for a refresher course. But if he does, Alcantara will simply fill the breach instead. And if Alcantara fails, Russell will likely be ready for his close-up by June.

Russell, Baez, and Alcantara all came up as shortstops, and all have the defensive chops to move around the infield, or even the outfield — Alcantara started 48 games in center for the Cubs last year and graded out well above average defensively even though he had never played the position before 2014. The trio’s defensive skills may eventually push Bryant, hardly a poor defensive third baseman himself, to left field.14

The defensive versatility of the Cubs’ roster makes hiring Maddon, a coup under any circumstance, particularly beneficial. While in Tampa Bay, Maddon would seek matchup advantages as aggressively as any manager in baseball, engaging in multi-position platoons by shifting someone like Ben Zobrist between second base and right field as needed. The Cubs’ roster is perfectly suited to this Team Pretzel concept, and Maddon is the perfect guy to take advantage.

If Olt, a former top prospect15 who is getting one more chance at third base in Bryant’s absence, starts hot, we might see Bryant play left field against left-handed pitchers — moving Coghlan to the bench — and third base against righties. Montero and Ross both have huge platoon splits, and you can be sure that Maddon will use them accordingly. The linchpin to this whole strategy is Alcantara, whom Maddon has already compared to Zobrist for his defensive versatility, and who might start at four or five different positions — at second base most of the time, but in center or right if Fowler or Soler needs a day off, or at third base if Maddon decides the Cubs need an extra left-handed bat against a particularly tough right-handed starter.

The Cubs’ depth of young talent will aid them as the season goes on, both directly and indirectly. Directly, in the form of prospects like Russell, who will probably be up after the Super-Two arbitration deadline in June, and has the talent to make an instant impact whether he fills a hole or simply adds to Maddon’s armamentarium of options. And in youngsters like right-hander C.J. Edwards, the no. 38 prospect in baseball and the top arm in the system, who could provide an electric, fresh arm in either the rotation or the bullpen for the season’s second half.

And indirectly, because if the Cubs stay within sight of a playoff spot into late July, they will have an enormous pile of prospects they can dip into to become buyers instead of sellers. Epstein and Hoyer have made it clear that sustained excellence is their primary mission and they won’t hamstring their future for a single playoff run. But the Cubs have so much prospect depth that even one of their second-tier chips could highlight a package for a soon-to-be free agent star. I haven’t even mentioned 18-year-old shortstop Gleyber Torres, the jewel of the Cubs’ massive investment in Latin America; or Jen-Ho Tseng, a right-hander signed out of Taiwan for $1.65 million in 2013; or center fielder Albert Almora and right-hander Pierce Johnson, the Cubs’ first-round picks in 2012. If, say, the Reds fall out of the race early and decide to put Cueto on the market before he reaches free agency, the Cubs will have the talent to get a deal done.

Even if the Cubs choose to play it conservative at the deadline, they’ll easily be able to target role players who fill any pressing needs. They have the payroll space to take on any short-term contract, and to absorb an overpriced contract if it adds talent without surrendering premium prospects. While Maddon is thinking up creative ways to use his young players on the field, Epstein and Hoyer can be creative in how they use their young players to build the strongest possible roster.

No one knows the future, not even Robert Zemeckis. No one owns a Grays Sports Almanac. But after the Cubs nailed the development process with so many players, unexpectedly got the opportunity to hire the perfect manager, inked the no. 1 starter they had lusted after for so long, and enjoyed every Bryant moon shot this spring, it’s increasingly clear that their run of sustained excellence will begin this year.

No one knows the future, but I’m calling it anyway: The Cubs are going to the playoffs. It may be a brief trip, and they may have to go through Miami in the wild-card game rather than in the World Series. But it looks like the Cubs will have a lottery ticket this October, and the other thing that no one knows is which ticket will be the lucky one.

The waiting is over, Cubs fans. Next year is here. Welcome to the future

of his young career. Heck, he’s 32nd in ISO overall, among our sample. For a young shortstop, Castro has quite a bit of pop.

of his young career. Heck, he’s 32nd in ISO overall, among our sample. For a young shortstop, Castro has quite a bit of pop.