Maybe you've noticed, but plants outnumber us. If they ever get a taste for eating animals, we could be in real trouble, even allowing for the whole mobility thing. Until now, we've thought of ourselves as pretty safe, since even carnivorous plants usually restrict themselves to a diet of insects and other invertebrates. Sadly we've been living in a fool's paradise, however, with the discovery of Canadian plants that dine on amphibians.

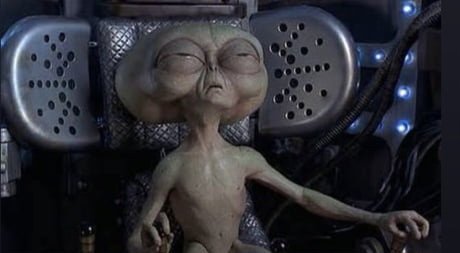

Pitcher plants are not as famous as Venus fly-traps, but the

Nerpenthaceae and

Sarraceniaceae families of carnivores are widespread in Asia and the Americas, respectively. Their leaves are shaped to make it easy for insects and spiders to fall in, and hard for them to get out. If they don't drown in water gathered at the bottom of the leaf, captives are broken down by digestive enzymes released by the plant so it can make use of their nutrients to compensate for nitrogen-poor soils.

Teskey Baldwin of the University of Guelph was studying the pitcher plants at Algonquin Park, Ontario as an undergraduate student in 2017 when he discovered something very unexpected – a salamander trapped inside the plant. Asian tropical plants have been reported consuming birds and mice. However, no one had ever reported a vertebrate getting this sort of treatment from a polite Canadian

Sarraceniaceae. Yet writing in the journal

Ecology, Baldwin and co-authors have found it is astonishingly common.

Indeed, in a survey of pitcher plants in one of the Park's ponds, 20 percent had a doomed salamander inside, and several had more than one.

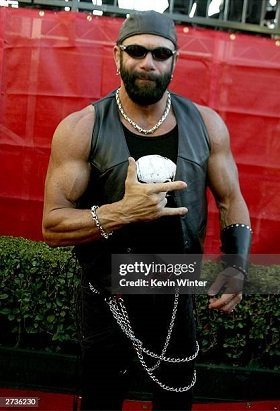

How this salamander got caught we will never know, but it's chances of getting out alive look bleak. University of Guelph

Algonquin Park is close to Toronto and Ottowa and heavily visited by botanists and sight-seers alike. As such many people must have seen the finger-long salamanders in the plants before, but no one before Baldwin thought it significant enough to bring to the world's attention. Partially this is probably an effect of timing – the study was conducted just after a “pulse” of salamanders had left the bog for the surrounding land.

Once trapped by the plant some salamanders lived as long as 19 days, while others were found to have died within three. The salamander's motivations for entering such dangerous territory is unclear. Perhaps they are fleeing other predators, or think they can snatch the invertebrate prey for themselves.

Baldwin and co-authors have dubbed the site the “Little Bog of Horrors”, a nod to

the musical about a meat-eating (

and singing) plant. Senior author

Professor Alex Smith suggested the visitor guides

should be updated to read: “Stay on the boardwalk and watch your children. Here be plants that eat vertebrates."

The authors are still keen to learn how important salamanders are to a balanced diet for pitcher plants, and whether some manage to escape.