Last hurrah with Bean. Tonight.

[h1]When the Celtics picked Antoine Walker over Kobe Bryant[/h1]

SITTING ACROSS FROM a reporter in a Denver hotel ballroom recently, Kobe Bryant listens to a story that is nearly two decades old but is new to his ears. As the story unfolds, Bryant's eyes widen. When it is finished, he calls it "the coolest f---ing story ever -- 'cause I haven't heard that story yet."

He then repeats this message -- sparing vulgarity this time -- to drive home the point.

"That's like the coolest thing I've ever heard, dude, because I grew up watching Red! You know what I'm saying? I read books about Red.

"I've never even known that he knew of my existence!"

BY 1996, M.L. CARR served as both head coach and executive vice president/director of basketball operations for the

Boston Celtics. Red Auerbach had ascended to become the team's president and presiding living legend. Not every decision merited a visit to Auerbach's office. But this wasn't just any decision, and that wasn't just any office.

No, Carr says, it was more of a "museum."

History covered nearly every inch of real estate along the gray walls of the corner space occupying the fourth floor at 151 Merrimac St., just a stone's throw from the then-FleetCenter (now-TD Garden). There were framed photos, plaques, paintings, plates, citations, trophies, magazine covers, a collage of newspaper clippings from 16 championships, a renowned collection of letter openers; plus maybe two dozen illustrations of the wide-grinned, cigar-chomping architect behind it all, Auerbach, a bona fide institution who, on the mid-June day that Carr stopped by, sat behind his large wooden desk, on which a sign read, "Think Big."

Auerbach had a way of thinking big. He fleeced St. Louis in 1956 to obtain the draft rights to

Bill Russell, snatched

John Havlicek with the last pick in the first round in 1962, drafted Larry Bird as a "junior eligible" in 1978 and orchestrated another lopsided swap that netted the Celtics

Robert Parish and

Kevin McHale in 1980. Any of these moves would lead a resume; in total, they made Auerbach legendary: 11 titles as a head coach, four as a general manager and another as team president, his role when Carr asked for his advice about prospects the Celtics were considering with their top-10 pick in '96, including a guard named Kobe Bryant.

The 6-foot-6 Bryant had wowed the Celtics in his predraft workout and awed them in a sit-down interview that Carr said was the best he had ever seen.

Auerbach had seen footage. He saw the glowing report compiled by the team's scouting director, Rick Weitzman, who declared, "There was nothing the kid couldn't do."

But there was risk. Bryant was making the leap straight from Lower Merion High School in suburban Philadelphia. Only a few players had even tried the prep-to-pro jump, namely

Moses Malone and Darryl Dawkins in the 1970s, but then the trend went on hold, only starting back up again in 1995 with

Kevin Garnett. What's risk to Red? He drafted the NBA's first African-American player, was the first coach to start five black players, the first to hire a black coach. He punched an opposing team's owner in the mouth, on the court, in a squabble over a referee's call. Boldness was no concern.

Auerbach and Carr talked about how well Bryant shot the ball. Carr raved about Bryant's institutional knowledge of the game. Auerbach waxed about Bryant's size and athleticism.

"I think this kid is going to be a hell of a player," Auerbach told Carr. "But it can go either way. He seems to be solid, but he's a high school kid. You've got to make a choice based on what you need today. But I think he's a hell of a player."

With that, Auerbach took a long draw on his cigar. It was said he smoked six a day -- he favored Hoyo de Monterrey -- and he especially loved lighting up a ceremonial stogie at the end of a blowout win, a tradition that was as much about celebrating as it was about taunting (and infuriating) opponents.

"OK," Auerbach told Carr, "now it's up to you to make a decision."

WHAT COMES TO mind first? The color.

"The Celtic green," Bryant says with a grin.

There he stood, at Brandeis University, about nine miles west of Boston, due to work out for the Celtics' braintrust, that green staring him in the face. He knew that specific shade well from his youth, when he devoured VHS tapes of Lakers-Celtics Finals from the 1980s that his grandparents sent him when he was growing up in Italy. Just as Bryant grew to love the Lakers, he came to loathe their bitter rival, an organization he considered an "Evil Empire" of sorts.

"Dude, that was the freakiest s--- I've ever [done]," Bryant says, shaking his head in near disbelief as he reflects. "I don't know if it's the mythology of the Celtic green or whatever, but they bring out the practice gear and you open it up and the shorts are there and it's like the green glows. It's like a different kind of a green.

"I'm looking at it like: 'Do I really have to put this on? I'm comfortable wearing the s--- that I have.' But I quickly moved past that, man. It's like, I'm quickly about to become a professional. If anything, I understand the history of this franchise, and this franchise has done a lot of amazing stuff. So I was quickly able to move by that."

Celtics assistant coach Dennis Johnson, who won two championships with the team during the 1980s (including one over the Lakers in 1984), ran the workout, one of about seven predraft workouts that Bryant said he completed that summer leading up to the draft, including two with the New Jersey Nets and two with the

Phoenix Suns. "To see Dennis Johnson out there was like the coolest thing in the world to me," Bryant adds.

About a dozen Celtics staffers watched with great interest in the gym that day, though Auerbach was not one of them. Bryant didn't disappoint.

"I tell you, he put on a shooting exhibition the way he stroked the ball," Carr remembers. "It was unbelievable. We put him in a lot of catch-and-shoot situations. We put him in dribble across the middle, pull-up-and-shoot. We let him stroke a little bit from the 3-point line. But it was a lot of quick release, get-it-off-quick [shots] to see if he could do that, because we knew at the next level, he was going to have to get it quick against better defenses than in high school.

"But he did it in flying colors."

Bryant's session reminded the Celtics of another high-flying guard.

"If you closed your eyes and thought a little bit, you might have thought you were watching

Michael Jordan," says then-Celtics general manager Jan Volk. "He did everything well -- beyond well. He was exceptional in everything that he did. And then we commented, as I recall, on how reminiscent he was of Michael."

"I can't think of any other way to describe his workout," says Weitzman, "other than he was exceptional."

"One of the questions that I got was, 'How will you get better during the season?' Because it was like, they knew, 'Well, if he comes in and he's not ready, how's he going to handle that?' [The] schedule was much different than it was in high school. You really don't have too many practices and all this other stuff.

"I just said: 'When I dream, I dream of basketball. When I wake up, it's the first thing I do. It's like an all-day thing for me, and it's not going to stop.'"

-- Kobe Bryant

THE INTERVIEW WAS held at the Celtics' offices before a half-dozen or so professionals from the team's' coaching staff and front office. Auerbach was not present.

"When I tell you this -- and I don't like to say a lot of good things about the Lakers -- but I am absolutely telling you this straight-up: He was unbelievable in the interview," Carr says. "He was the best interview that I've ever been a part of. Kobe knew the league as well as anyone. He knew the Celtics from a historical standpoint. He knew the Celtics probably better than most Celtics did at 17 years old."

Carr says Bryant traced the Celtics' history from Russell through Bird. He pointed out various aspects of each player's game and broke down moves that made them special. He referenced specific playoff series and numerous Finals matchups. Carr says Bryant had an "incredible" understanding of the league -- not just of the Celtics but also of several other teams, including the Lakers,

Philadelphia 76ers and

New York Knicks.

"I was like, 'You've got to be kidding me!'" Carr says. "Quite frankly, some of this stuff, I didn't even know. I'm sitting there listening to him go through it. And I remember [Celtics assistant coach] K.C. Jones, we were talking about it, and he goes: 'He's a student of the game. He understands the game. And he's appreciative of that.'"

Volk describes Bryant as being "very poised" and "very well-spoken" during the session. Volk adds that Bryant was "clearly mature beyond the expectations typical for a high-school player." The interview lasted for an hour, about twice as long as their interviews with other prospects.

"He said all the right things. He sounded like a Celtic."

M.L. Carr on Kobe Bryant in 1996

"He didn't mention rings, but he talked about Michael," Carr says. "He talked about Larry. He talked about Magic [Johnson]. He talked about Isiah [Thomas]. He talked about the great ones. You knew there was a hunger to be in that mix. He knew what all those guys had done. He wanted to be one of those guys that would be talked about in that same breath. There was a hunger. No question, there was a hunger."

Deep down, Bryant was a die-hard Lakers fan, but the Celtics say they weren't aware of that at the time -- nor did Bryant relay that fact to them at any point. "Kobe didn't give that up in the interview," Carr says.

Says Volk, "We had no reason to believe he wouldn't play for the Celtics or whatever team would draft him."

"He never said, 'Do anything you can do to get me.' He said, 'I would love to be with the Celtics,'" Carr says. "It wasn't anything over the top other than, 'I would love to be a part of this great tradition.' He said all the right things. He sounded like a Celtic."

FOR ALL THE Celtics' tradition, at this juncture, Boston was a 33-win team searching for direction and looking to the 1996 draft for salvation.

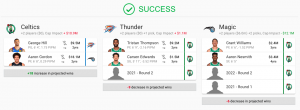

Boston's analysis was similar to many teams': the draft had six can't-miss prospects. The "Super Six of '96," as they came to be known:

Allen Iverson, Marcus Camby, Shareef Abdur-Rahim,

Stephon Marbury, Ray Allen and

Antoine Walker.

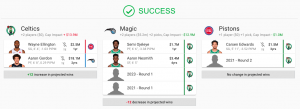

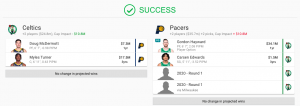

The Celtics had the ninth pick in the draft, but they cut a deal to move up to the sixth pick, guaranteeing one of those players.

"We worked our butts off to get in a position where we could be in the top six," Carr says. "My eye was on Antoine because I knew that watching him -- [and] Kentucky had just come off a championship year in college -- [that with] his skill set, he could be an incredible impact player."

"We didn't care which one of the six fell to us," Weitzman says. "We knew we would take one of them because we needed help right away and all six of those guys were prepared to help right away, whereas Kobe, we knew we'd have to wait. And you know how the NBA works -- you don't have a long leash."

WEITZMAN HAD MORE than a dozen years of scouting experience at the time, almost all of which came from watching college juniors and seniors. But, suddenly, prep players started jumping to the pros again, which presented a new challenge.

"The thing you have to realize is how difficult it was to evaluate those guys," he says.

For example, if Weitzman scouted a Kentucky-Duke game and one player stood out, he knew that player was special because the competition was close to NBA quality. As it was, if college players were one step away from the NBA, high-school players were two steps away, which meant having to project further down the road what a player might become.

Along with other scouts, Weitzman didn't have much experience scouting prep players when he saw Bryant. Still, Weitzman had heard that Bryant "was a terrific talent." He also had seen plenty of Bryant's father, Joe, a forward who played eight NBA seasons with the Philadelphia 76ers, San Diego Clippers and

Houston Rockets. "I knew the genes were there, but I was very curious to see what the product was like," Weitzman says.

So he visited Lower Merion to watch Bryant's squad take on a suburban Philadelphia team. A Knicks scout attended the game too.

"Kobe came out and did basically whatever he wanted to do," Weitzman remembers. "I only saw him once in high school, but that was all I needed to see."

He adds, "I told the higher-ups that the kid was a tremendous talent, [had] tremendous potential, outstanding approach to the game, but he probably wouldn't be ready to contribute to an NBA team for a couple years, which ultimately proved pretty accurate.

"We couldn't afford to wait, unfortunately."

AFTER CONSULTING WITH Auerbach, the final decision was Carr's, who understands history, in this case, could "sound like an indictment on me."

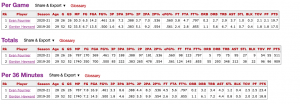

Carr chose the 6-foot-8 Walker, who certainly had the talent to lead an NBA team. In eight seasons in Boston, Walker averaged 20.6 points, 8.7 rebounds and 4.1 assists, became an All-Star in his second season and twice more during his Celtics tenure. He helped the Celtics thrice reach the playoffs, including the 2002 Eastern Conference Finals.

But Walker, obviously, can't be viewed as a legend in the mold of Bird or, indeed, Bryant.

Bryant fell to the 13th overall pick, where the

Charlotte Hornets drafted him before dealing him to the Lakers in exchange for center Vlade Divac, a move that is now considered a stroke of genius by former Lakers general manager

Jerry West.

Leading up to the draft, Carr says he had several conversations with West, but he had no idea West had any interest in Bryant.

"That's why he's such a great general manager," Carr says. "He wasn't going to give that away."

Carr adds: "I think this is as much as a thumbs up for Jerry West as it is for the fact that Kobe went on to do what he did. Jerry, he had some uncanny knowledge of how this all works."

Says Volk, "Kudos to the Lakers, who not only took a chance, but moved to get there and made a substantial trade to get in position."

Of course, Bryant went on to have a better career than not only Walker, but everyone else in his draft class, of which Bryant is the only one still playing.

Looking back, Weitzman says, "It was impossible to project that he'd have this great a career and this great an impact on the game from that point. Anybody who tells you differently is not being realistic, because there's no way of telling how good a player is going to be until he gets into the NBA and gets it done."

"I suspect there are other teams who have regrets as we did in time because he clearly showed to be a missed opportunity for us," Volk says. "Whether or not we were prepared to take a high-school player at that particular point in time, that's hindsight and very difficult to comment on now. But I suppose if there was ever one, he was it."

"We all liked him. There was nothing not to like," Weitzman says. "[And] M.L. loved Kobe. He absolutely loved him. And he was very tempted to take him."

TODAY, THE MERE mention of "Super Six of '96" perturbs Bryant.

At the end of Kobe's predraft workout in Philadelphia, then-76ers assistant coach Maurice Cheeks asked Bryant to run from baseline to baseline while Cheeks timed him. Bryant recorded an excellent time.

But then Cheeks told Bryant that Iverson had run it just a bit faster.

The 76ers held the top overall pick, and they eventually used it on Iverson.

"And being the bullheaded kid that I was, I said, 'What the f-- does this have to do with playing basketball?'" Bryant says. "I think that moment right there is when the frustration came out for me, because I felt like I had watched these players and I knew I could compete with these players, and I knew inside, I had a passion for the game that supersedes theirs. As you could tell, it still itches at me. It's like, dude.

"So I was very, very conscious of it."

Bryant had another perception problem too: The only successful prep-to-pro players to that point -- Malone, Dawkins and

Shawn Kemp, who enrolled at Kentucky and junior college but never played -- had been big men.

"It's a fight I've dealt with my entire career," Bryant says. "Even in high school, going to All-Star camps and having the player rankings come out, they would always say, 'If there is something that's remotely close, we'll always tilt to the big guy. So it was always that s---, all the time. Big guy. Big guy. Big guy. Big guy.

"And it drove me crazy."

"I would've tried to carry on Bird's legacy. Absolutely. I would've done it with a tremendous amount of pride and honor."

Kobe Bryant on if the Celtics had drafted him

Carr recalls the meeting when the Celtics decided not to pick Bryant. "We all looked at each other," Carr says, "and we knew there was a possibility that Kobe could come back and haunt us. We knew that."

Bryant smirks when he hears that, pleased that he managed to complete the haunting. Bryant says his favorite title was his fifth, when his Lakers beat Boston in a grueling seven-game series in the 2010 Finals.

"It's the sweetest because it was the hardest," Bryant says of that 2010 title, which avenged a 2008 Finals loss to the Celtics. "I still sometimes think, how the hell did we win that series? That series was brutal. Physically demanding. Psychologically extremely stressful."

He remembers one off-court moment in particular. The teams had split the first two games in Los Angeles, and Bryant recalls crossing paths with members of the Celtics' families at the airport on the way back to Boston.

"As I'm sitting there on the plane and I'm looking at the families, just so comfortable, just so carefree, just kind of joking because they got a split, they're going back to Boston," Bryant says. "And just watching the sheer joy of them getting on the plane -- contrasting that with us getting on the plane, being in complete misery. It was like, 'Man, I'm going to make them f---ing eat this s---.'"

Bryant also beat Iverson and the 76ers in 2001. Those two Finals are among Bryant's proudest achievements.

"Those sort of things meant a lot to me," Bryant says, "because it was like, I get a chance to really prove I did it."

WHAT IF THE Celtics had drafted Kobe Bryant?

"I would've tried to carry on Bird's legacy," Bryant says without hesitation. "Absolutely. I would've done it with a tremendous amount of pride and honor."

Bryant's reverence toward Bird might come as a surprise to some, given the Lakers-Celtics rivalry, but Bryant says he studied Bird just as much as he did Magic and Jordan.

Anything specific?

"Timing. Reading situations. Tenacity with his teammates," Bryant says. "I've really studied. That's like the holy trinity for me -- Bird, Michael and Magic. I really watched everything about them."

And of Bird, Bryant says, "You have no idea how much I've studied this guy. Oh, man."

Bryant also raves about Auerbach, the Celtics' patriarch. "I read everything about him," Bryant says. "One of the things that I thought was really cool was how he created the legacy with the Celtics franchise. In other words, the players that he brought in eventually get older, and then they feel a sense of intimidation and insecurity with the younger group coming in. So Red just changed the culture by changing the dynamics and saying: 'Listen, you train them. As a result of you training them, you're here forever.'

"It's that little twist [that] enabled them to win year after year after year. Even though this generation of players is getting older and they're phasing out, they train them to win in that same way and now here they come. And in turn they do the same thing. As a kid watching that and reading that, stuff like that, little things like that, I've always picked up."

In an interview, Carr asks that a tongue-in-cheek message be relayed to Bryant. He wants Bryant to know that a month or two after he retires, he'll have second thoughts, an itch to come back.

"When he comes back, tell him to come back with the Celtics," Carr says, "then he can win championships on both ends of the rivalry. Tell Kobe it's never too late! Tell him that we'll make him bigger than big."

Bryant bursts out laughing when informed of Carr's message. To put it lightly, it seems such a scenario is out of the question.

"Just a little bit," Bryant says between laughs. "Just coming back period is out of the question. Let's deal with that first obstacle, let alone the second one."

Just the same, Carr had more than a few hearty laughs when recalling why exactly he passed on drafting a player who became one of the greatest ever.

"We weren't sure if it was going to translate with Kobe to the next level," Carr says.

"Well, guess what -- that's the understatement of the century!"